McEwan has come a long way from these ghoulish works, and so have we. Especially in the last four years. In the wake of 9-11, Jonathan Lethem aptly pointed out that we just witnessed a spectacle so large it trumped imagination. The question for novelists remained not what would they do to top it—that, after all, would be more than ghoulish—but how would they write about it.

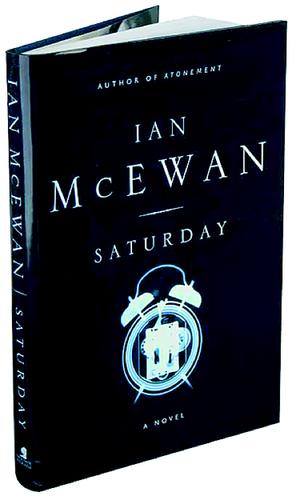

Saturday, McEwan's latest timepiece of a novel, is one answer. With deceptive boldness, the novel writes itself right into the present tense, unfolding over the course of a single day in February 2003, as England prepares for war in Iraq, and wealthy neurologist Henry Perowne gets ready for his squash game.

That funny juxtaposition says a lot about where this novel is about to go. There may not be any supernatural elements to Saturday, but there is menace. For starters, Perowne, the book’s voluptuously good-fortuned hero, has a bit too much going for him. He drives a Mercedes and lives in a design-magazine fantasy home. He has a good wife and a happy family. His taste in food is fantastic.

But from the moment Perowne wakes, something is off. In the middle of the night he climbs from his bed and pads to the window, where he sees a plane making what appears to be a fiery crash landing at Heathrow airport.

This strange moment casts a pall over the coming day, during which Perowne expects visits from his daughter and his eminent father-in-law. As Perowne sails forth into the morning—making breakfast, climbing into his Mercedes to go play squash—he carries this alarming moment with him like a wave of anxiety.

Not surprisingly, like Virginia Woolf's Clarissa Dalloway—another fictional character shopping and trying to enjoy life on the eve of a war—that feeling echoes back to him. An anti-war demonstration rages on, blocking traffic and steering Perowne into a fender bender that nearly leads to an altercation with a mentally unstable man.

That ping you just heard is the coil being sprung for McEwan's plot. Saturday is, at the heart of it, a tale of two brains, both struggling to absorb the anxiety of our new world. One of the brains belongs to the violent man Perowne has the car accident with, the man whom he can diagnose but not control. The other brain belongs to Perowne's mother, who suffers from vascular dementia, a condition that has robbed her of her memory.

Although Saturday is more contemporary, more cinematic than anything McEwan has published to date, it does have a significant relationship with his recent work, specifically Atonement, the sprawling novel McEwan published in 2001 about a child’s fib that destroys a man’s life and makes her a writer in the process. Saturday is the adult counterpoint to Atonement, providing a wintrier look at the question of consciousness and writing.

Throughout the day, Perowne recalls the books his daughter, Daisy, a budding poet, instructs him to read: Madame Bovary, a biography of Darwin. None of them moves him. To Perowne, literature is a work of accretion, not genius, and it certainly doesn’t give him access into the heads of other people. For that he has his knife.

This is a very cerebral sort of reckoning to pitch one's character into, which is why it feels somewhat abrupt when, three-quarters of the way into the novel, Perowne winds up in a situation of true danger. It's as if by merely thinking of them Perowne can conjure his worst fears.

That, in a way, is part of the point of Saturday, a beautifully arranged novel about the way nightmares spring from out of our mind—and filter back into it. How do we deal with this? How do we reckon tragedy and death larger than life?

With Saturday, McEwan has set out to atomize a man’s empathic response to these questions when he believes in neither religion nor art. It is not just a book about a man watching himself think; it is the story of a man watching himself feel, too. Amazingly, the novel convinces us the two can be one and the same.