When will it end?! Well, it won't, really—at least, not until humanity finally succeeds in exterminating itself. Certain people feed off outrage like a dachshund feeds off Gravy Train. It's just part of modern American life. We might as well just get used to it.

Of course, at least since the '60s there have also been provocateurs within our ranks who go out of their way to offend. Many people assume that weekly alternative papers like the Alibi fall into this class. Hardly. We're really quite wholesome once you get to know us. Compared to the work of R. Crumb—one of the grand masters of offensiveness—the Alibi reads like a Norman Rockwell calendar.

For better or worse, Crumb grew up with a tyrannical older brother named Charles who forced all five Crumb kids to immerse themselves in the world of comics as soon as they were old enough to hold a pencil. For this reason, throughout his childhood Crumb was a comic-making machine. As an adolescent, this unfortunate obsession placed him firmly in the dork camp. Anxiety, social backwardness, sexual frustration and existential trauma followed. By the time Crumb clambered his way into adulthood, he was a shivering neurotic mess.

Crumb has had a miserable life, to be sure, but he wears that misery like a badge of honor, mainly because there's no way he ever would've become a world famous artist without it. After a short stint at a greeting card company, Crumb headed out to San Francisco in the mid '60s. He dropped a bunch of acid, jumped into the free-love counterculture headfirst, and eventually started doing really freaky, far-out comics for underground hippie magazines.

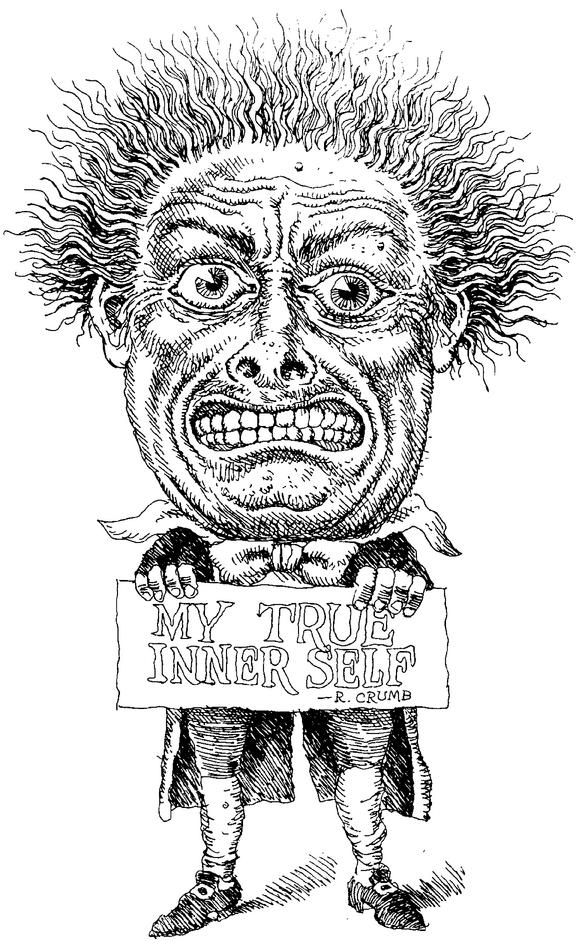

Crumb isn't the sort of artist who edits his ideas. He vomits them up on the page without a thought to conforming to mainstream sensibilities. Disgustingly, a large quantity of his ideas have revolved around perverted fantasies involving large females. In interviews, he's admitted to having problems with women in general, and it shows. One of the most disturbing aspects of his work is that so much of it seems openly misogynistic.

Crumb has also done a large number of comics that he claims are social satires but that come across to many people as blatantly racist. Other Crumb pieces are revolting because they involve graphic violence of a kind that you'd never see in a million years in a mainstream comic.

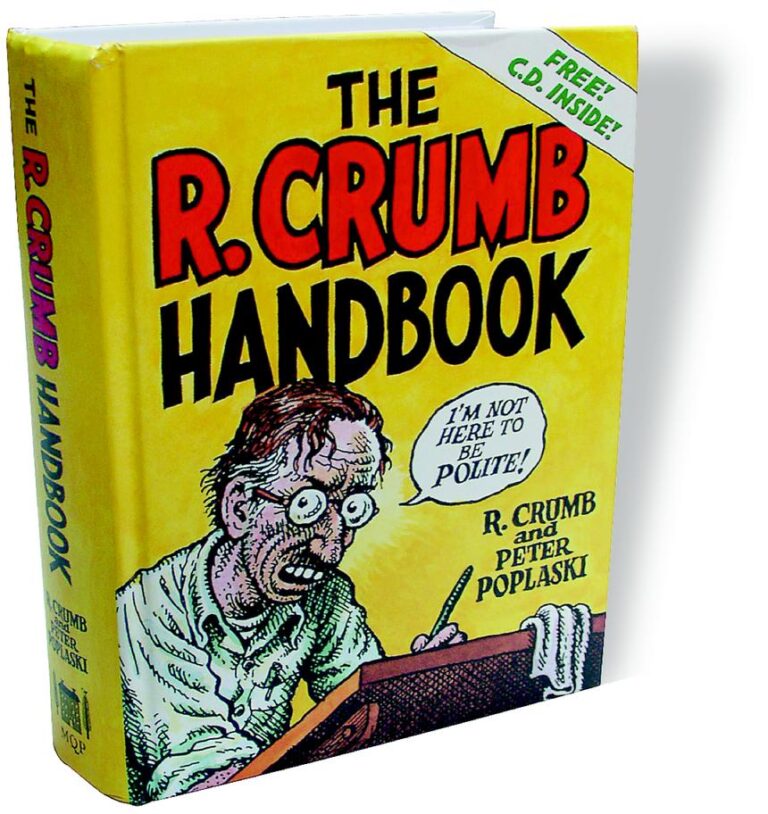

So why is this creepy weirdo so absurdly famous? The R. Crumb Handbook does an admirable job of making the case for Crumb's legitimacy as an artist. It incorporates many of his most disturbing comics, and, although it doesn't make them any less disturbing, it succeeds in portraying Crumb as a sincere social critic and satirist.

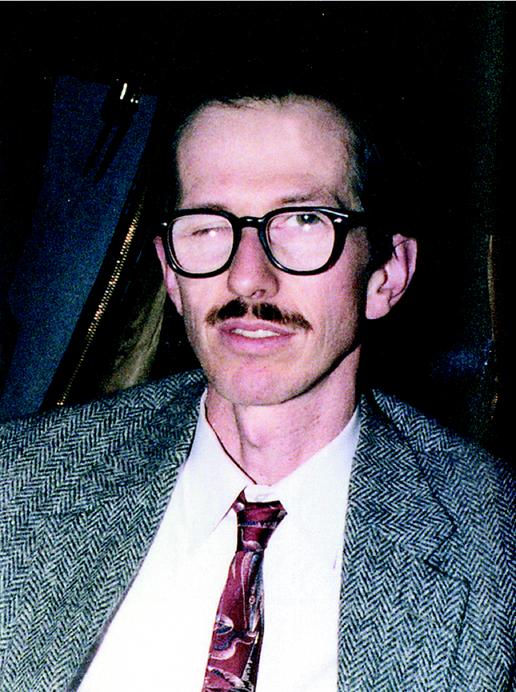

There are lots of photographs here and some new Crumb comics as well. There are also plenty of quotes from critics, cartoonists, family members and others eager to open a window into the demented mind of the artist.

One of the finest aspects of the book is a series of essays in which Crumb expresses his own thoughts on his life and art. He's surprisingly thoughtful and articulate, especially when commenting at length on the mainstream culture that's simultaneously been hostile to his work and placed him on a pedestal as some kind of visionary counterculture antihero.

Poplaski and Crumb decided to divide the book into four sections based on the Toltec Indians' traditional “four enemies of man”—fear, clarity, power and old age. At first, this seems like a bizarre conceit, but, given the nature of Crumb's work, by the end of the book this structure seems perfectly logical.

Even if his comics still disgust you and his essays don't sway you, the “free” CD included in the package might give you a tinge of sympathy for this screwed-up little man. One of the quirks of Crumb's personality is that he seems to hate everything about modern life. For this reason, he's cultivated an obsession with old-time music that often creeps into his art. Over the years, he's amassed an enormous collection of 78s from old blues, jazz and Appalachian performers of the '20s and '30s. He's also played in numerous string bands since the early '70s.

The CD includes 20 recordings of Crumb's music from 1972 through 2003. Much of it is surprisingly good and only a couple songs are rude in any way (e.g. “My Girl's Pussy,” according to Crumb a traditional Appalachian ballad). The CD is a funny little artifact, but it also highlights an important aspect of Crumb's worldview. In a strange way, he's always been a nostalgic artist, romanticizing the past because the present and the future make him anxious and paranoid.

Crumb's getting older. He's now in his 60s. He's married. He's got two kids. He admits to becoming more conservative in his old age. He also admits that some of his most brutal comics sometimes embarrass him when he reads them now.

This detailed 400-plus page book reveals a wiser, more sympathetic Crumb. In some ways, The R. Crumb Handbook expands on Crumb, an incredibly entertaining documentary released in 1994 that digs into the familial roots of Crumb's bizarre artistic vision. In both book and film, Crumb admits to having a gigantic ego. With this in mind, The R. Crumb Reader, like the documentary before it, seems like a deliberate attempt to manage his legacy. Crumb probably doesn't have that many years left. (One look at his frail body makes you wonder how he managed to live this long.) He obviously wants his art to last, and he wants to explain to the culture that both embraced and spurned him why it should last.

I don't know whether the book—or the movie, for that matter—succeeds. Despite his incisive satirical skills and undeniable graphic talent, much of his art is still totally revolting. Yet The R. Crumb Reader makes a strong case that Crumb's work successfully delves into the darkest corners of our psyche and society. Crumb seems to argue that it's our current, commodified, hypocritical, money-obsessed society that's truly revolting, not his demented little comics. Looking around us at all the absurdities of modern life, it's hard to argue with the man.