By contrast, Villages tells the story of a man's journey into the world, not through it, and he does not emerge from the tale with a greater understanding of himself. In fact, Owen Mackenzie, Updike's septuagenarian protagonist, departs this limpid, curiously sad book with greater doubts about his life. Was he a good husband or lover? What was it that fascinated him so about the other sex? Were his parents truly in love?

It's a subtle difference, but in that tweak of the classical bildungsroman one discovers everything great and distinctive about Updike as an artist. His novels and stories have endeavored to capture the texture of lived experience. But no matter how many million words Updike marshals to describe human interaction, there remains something mysterious and just-out-of-reach about it. One presumes this is what keeps Updike writing when his card page has bulged to over 50 books; and it's what keeps his protagonists vaguely unhappy when they have every right to be content.

In keeping with the bildungsroman tradition, Villages closely follows the physical and emotional trajectory of its author. Like Updike, Owen grows up in Pennsylvania, has a brief detour to New York, and then settles in New England. His emotional journey is similarly familiar, involving, as did Updike's, early marriage, children, divorce, a second marriage, and then comfortable domesticity.

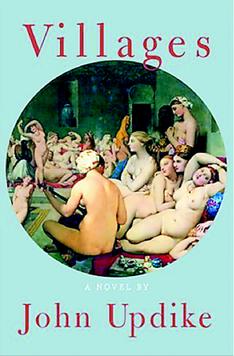

As the book's title suggests, Updike would like to show how the villages of Owen's life have shaped him, made him who he is today. In actuality, the book should have been called Women, for it is the women of Owen's life—not one township or another—who make the most piercing impressions. From his lovers, Faye and Alicia, to his first wife, Phyllis, these are the people spelling out Owen's emotional zip code and he remembers them well.

This constellation of feminine figures is not a new thing for Updike. His novels have always drawn their great crackling energy from the erotic presence of women. It was the women in Couples who received Updike's most lavish attention, even if they were seen so often through the eyes of men. If anything, Villages is a companion volume to Updike's darkest and most mandarin of such novels, Toward the End of Time, in which a man sits in a similar New England perch surfing through the years, remembering sexual escapades and marveling over the passage of time.

While that novel emitted a sourness that bordered on misanthropy, Villages feels wholesome and nearly calming, the blanket of years falls upon Owen like a 1,500 thread-count balm, lulling him into a kind of waking dream. From the distance of years, Owen remembers all those hiccuping orgasms and teary fights and wonders what all the drama was about.

Readers who have had trouble with Updike's portrayal of women will, with this novel, have plenty to gripe about. An anthropological tone creeps into Updike's prose that is not entirely flattering. Even when he appears to be going out of his way to acknowledge what some have perceived to be his deficits in writing about sex, Updike sounds aloof, scientific. “A sexual transaction was a psychological transaction,” Owen thinks at one point, “one must feel the other, however ideally submissive, has a psychology, a mind registering events somewhat in parallel. Otherwise we are stuck with the sordid pathos of the inflatable female bodies.”

At the same time, it is unfair to criticize Updike for writing about men who think this way; men who compartmentalize, who fantasize, and then retreat into boroughs in their mind that are inhabited by women other than their wives. After all, this is how some men live, in spite of the crisp order of their suburban streets, their green front lawns. With this elegant, if cold, new novel, John Updike proves once again that no one knows these secret villages better than he.