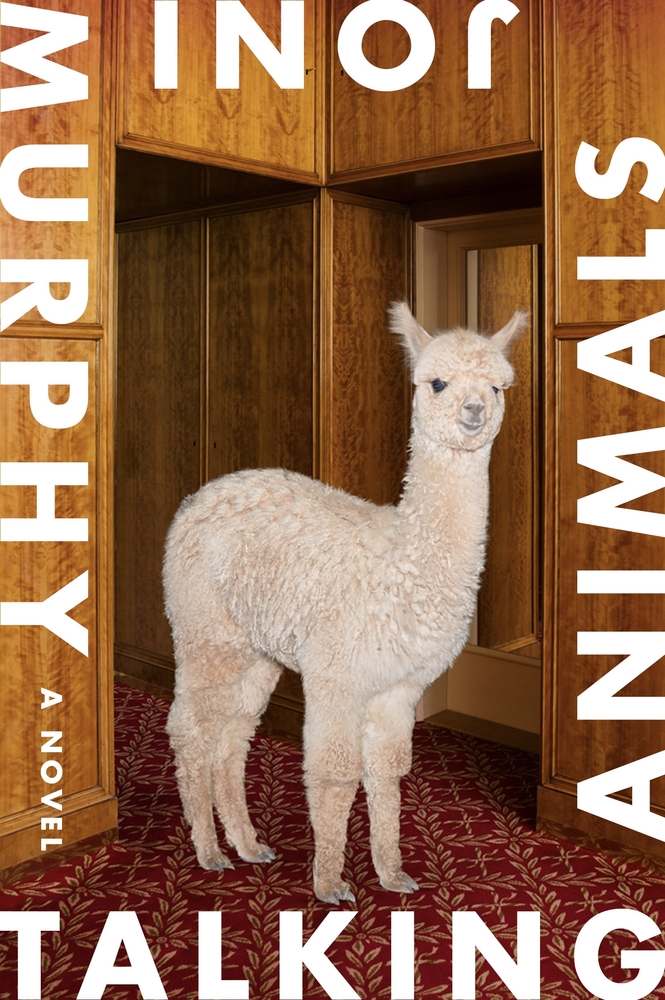

Joni Murphy’s Talking Animals

An Orwellian Satire About The Revolution That’s Already Here

Courtesy Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992

Courtesy Farrar, Straus and Giroux