This kind of spirituality grew out of humbleness, not wealth. It helped communities survive nature's whiplash and keep going. Folks didn't join the church to social climb or to jump the queue to heaven; they came for a stay against confusion.

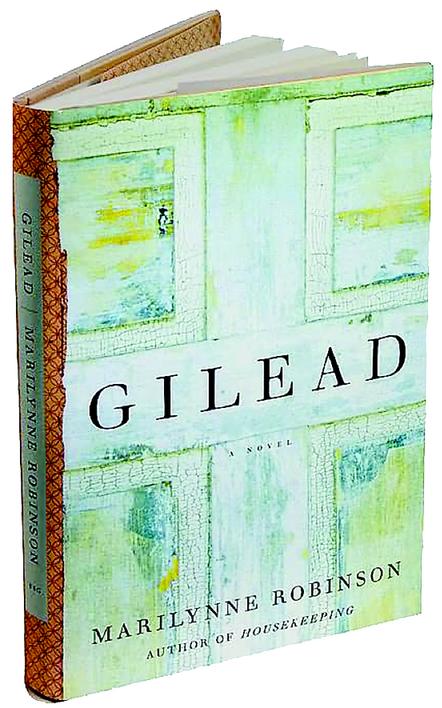

It's the sort of grappling with belief that takes center stage in Marilynne Robinson's second novel, Gilead, winner of both the 2005 National Book Critics Circle and the Pulitzer Prize.

Although the date on its copyright page reads 2004, Gilead feels like it could come from any point between 1880 and the late '50s, bookends for the life of its eloquent narrator, John Ames.

Born and raised in the small town of Gilead, Iowa, Ames is now dying of heart disease and Gilead forms the account he will make of his life to his 7-year-old son. He wants to tell his boy about baseball and women, about his father and the woman who became his wife. There is so much to say and so very little time to say it.

So Ames writes it all down, as well as he can, which is very well indeed. Unfolding in a series of short to medium-length set pieces, Gilead weaves a mesmerizing spell from the most homespun Americana. Ames talks of ancestors past and dead, of eating fried egg sandwiches alone during nights spent listening to baseball over the radio.

After losing his first wife and daughter in childbirth, Ames expected the rest of his life would go this way—his loneliness cut by the high pressure system of a once-a-week Sunday sermon to complete. But then one day a younger woman entered his church and the 67-year-old Ames fell in love.

In the Bible, Gilead has a multitude of meanings, from the land east of Jordan, which is thought to be a source of salve, to the Old Testament rendition of the region which can mean a war-like place. Robinson plays off these meanings in her novel deftly and elliptically, ultimately crafting a poignant tale of fathers and sons.

Ames' father never made amends before learning his father had died, impoverished and far from home. In punishment, he wrestled with guilt until the end of his days. Gilead opens with Ames remembering the trip he and his father made across the plains to find the old man's gravestone.

In Gilead, Ames makes a similar journey in search of cross-generational communion, but the distance is traveled by prose this time, not by foot. It is mythic territory, indeed, but also dangerously close to sentimental.

Minus a few unnecessary lyric flourishes, however, Robinson keeps Ames' voice expertly modulated—searching, without being needy, unassuming yet never falsely coy. It has been 23 years since Robinson published her first novel, Housekeeping, and every one of her past narratives can be felt in the perfect authority of Ames' voice.

What cannot be accounted for with experience alone, however, is the quality of Ames' rapture for the world. Robinson marshals each sentence of his here with reverence and care. The details practically glow on the page.

In the end, it's hard to tell whether Gilead is a prayer or a book, a confusion Ames encourages at the start of his story. “For me writing has always been like praying,” he says. “You feel that you are with someone.”

Read Gilead and you will feel similarly inhabited. At the very least, you will know this man. His name is John Ames. He was born in 1890. This powerful book is his story.