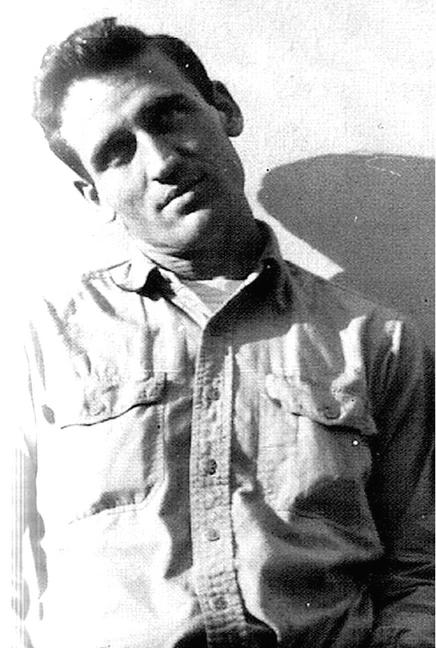

The same goes for writing, and there is no playground legend in America quite so tall and floridly embellished as that of Beat-era writer Neal Cassady.

A pool-hall hustler, gifted athlete, expert car thief and pornographic womanizer, Cassady was the real McCoy. He was Beat without trying. He was born into near-poverty in Salt Lake City, Utah in 1926, grew up on skid row in Denver, and wound up in New York in the '40s when Jack Kerouac and company were dropping out of Columbia University.

While his friends were unmooring themselves from academia, Cassady had been born free of middle-class expectations, and they envied him that. It was as if a character from their fictional imagination had blown down from the high plains and right into their lives. Here he was—a devotee of impulse, a smokestack of language, a saint of motion.

And so they made him a hero. In John Clellon Holmes’ Go (1952), the book often cited as the first Beat novel, Cassady shows up as “Hart Kennedy,” the motion-mad yelper who energizes parties. In Jack Kerouac’s On the Road (1957), he is Dean Moriarty, the holy goof famous for, among other things, his ability to park cars.

He was “the most fantastic parking-lot attendant in the world,” Sal Paradise says in On the Road. He “can back a car forty miles an hour into a tight squeeze and stop at the wall, jump out, race among fenders, leap into another car, circle it fifty miles an hour in a narrow space, back swiftly into a tight spot, hump, snap the car with the emergency so that you see it bounce as he flies out; then .?.?. leap into a newly arrived car before the owner’s half out, leap literally under him as he steps out, starts the car with the door flapping, and roar off to the next available spot, arc, pop in, brake, out, run.”

Although Cassady became a kind of bop musician of motion—he worked as a brakeman on the Southern Pacific Railroad and drove Ken Kesey’s magic bus in the late '60s—he was not satisfied by it. As all the Beats knew, what he really wanted to do was write.

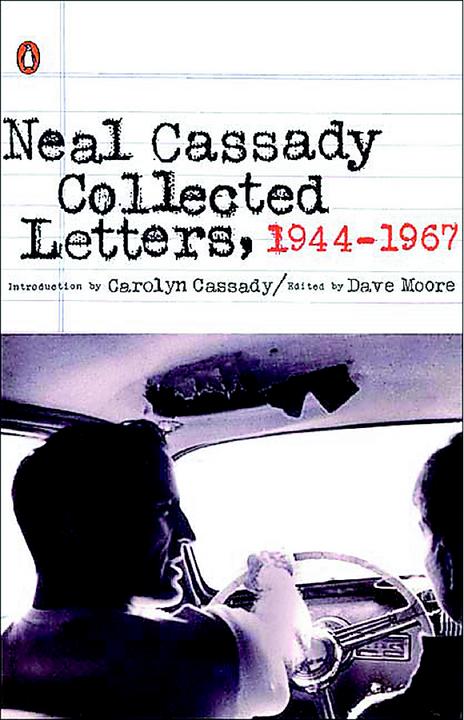

Nowhere is that desire more apparent than in Collected Letters, 1944-1967, Dave Moore’s hefty and intelligently edited volume of Cassady’s dispatches to Kerouac, Ginsberg and a great many of Cassady’s on-the-sly paramours. Carolyn Cassady herself contributes an elegant and spry introduction.

Here they are—all those infamous 13,000-word letters Kerouac and Ginsberg ranted about, tales of wooing girls on cross-country buses hustling along the page like the rat-a-tat output of a ticker-tape machine. Read them and you realize it was no accident Kerouac wrote one of his drafts of On the Road on a teletype roll. He was imitating Cassady.

You would think this might be a heartening discovery. It isn’t. Collected Letters is a brilliant, tedious and funny book, one certain to make any office worker feel a bit square and too wedded to the day-to-day. But it is also a deeply sad volume, providing a window on Cassady’s life as he turns himself into a roman candle burning at both ends.

The wick is lit in 1944 with Cassady saying hello to mentor Justin Brierly from Colorado State Reformatory, where the 17-year-old Cassady was serving a year for receiving stolen goods. What’s immediately striking is Cassady’s great eloquence and desire to learn. Indeed, after he was released, Brierly discovered Cassady had an IQ in the low 130s. When Cassady first arrived in New York in 1946, he brought with him a young wife, a volume of Proust and a warrant for stealing a car in Nebraska. It was on this trip that he first met Kerouac and William Burroughs—and Allen Ginsberg, with whom he had an affair.

One of the surprises of Collected Letters is how earnestly Cassady felt about Ginsberg, or professed to feel. In one letter, after confessing that his early sexual experiences with other men had felt forced, Cassady tried to shake Ginsberg off by offering up a communal arrangement: “Allen, this is straight, what I truly want is to live with you from September to June, have an apt., a girl, go to college … see all and do all. Under this arrangement we would have each other, a girl, (this is quite similar to you, Joan & Bill) and become truly straight, (thru analysis, awareness of ’sacrament' and living together).”

Here was free love in its messy, turbulent infancy—the penumbra of post-War American wholesomeness already bearing down on them. Later that year Cassady would meet Carolyn Robinson, who became his second wife in 1948, seven months before his first daughter was born. In 1950, she had a second child, a few months after he began an affair with another woman.

As much as this timeline makes him sound like a lout, it’s hard not to see the appeal in these letters. Many of them sound like an inmate asking for a faithful follower to break him out of prison.

Cassady was in fact a criminal—in some early letters, he offers to fence stolen overcoats for Ginsberg in Colorado, where he can get more money for them—but he was also a writer, and these letters tell great stories. Branded with a time and a place, each one stomps out of the gate at a bucking gallop and challenges the reader to hang on to the stallion belt for dear life.

The deeper we read into Collected Letters, however, the more Cassady’s grip begins to slip. “We are collapsing, so is everyone,” he writes to Kerouac in 1951. By 1955, after Carolyn had thrown him out for having yet another lover, he wrote home saying, “I hate myself & you know it, but I looked long & hard at my son last nite & I realize my responsibilities, plus I am in full fear of my feeling that once a man starts down he never comes back—never.”

Two years before Kerouac’s On the Road would be published, Cassady was already down. He’d begun gambling on horses. In 1958 he passed three marijuana cigarettes to undercover agents in San Francisco. He was sentenced to five years in prison, and served two. Upon release, he eventually found work as a tire recapper in San Jose, Calif., the same year Kerouac wrote his last great novel, Big Sur—itself a cautionary dirge to the excesses of their era.

Cassady would live another eight years. Meanwhile, the '60s arrived and the rest of the nation became clued in to a lifestyle he and his friends, for better or worse, had embraced for two decades. These letters are a fabulous artifact of that time. They are also a cautionary tale. After burning brightly for a short while, Cassady burned out. He was discovered dead by a set of railroad tracks in Mexico in 1968. He had consumed a mixture of alcohol and Nembutals, a combination known to be fatal. He was a few days shy of his 42nd birthday.