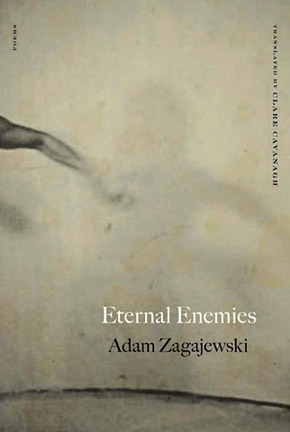

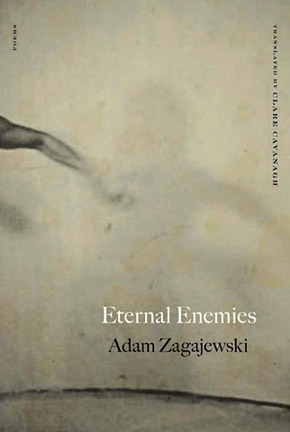

Poetry Review: Eternal Enemies By Adam Zagajewski

Eternal Enemies By Adam Zagajewski

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992