Sex Ape: Are Humans Ready To Learn From Our Most Promiscuous Cousins?

Are Humans Ready To Learn From Our Most Promiscuous Cousins?

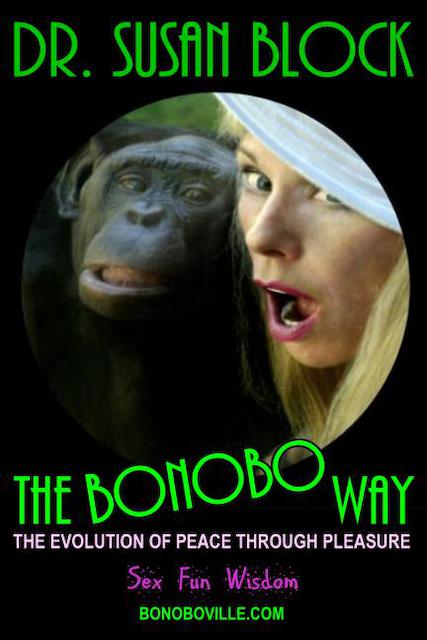

Dr. Suzy (R) channels her inner bonobo.

A couple of bonobos channel their inner Dr. Suzy.