Nemesis.

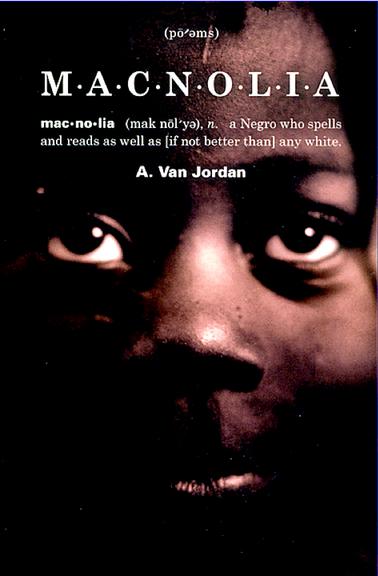

Although the word was an unfair selection—it might not have been on the approved list—the choice was apt, for that is what MacNolia’s skin color was to her back then. In his debut collection, M-a-c-n-o-l-i-a, winner of a Cleveland Foundation Anisfield Wolf Book Award, A. Van Jordan spells out an imaginary, but believable, inner life for the woman who nearly became the first black spelling bee champion long before Malcolm X began studying the dictionary in his prison cell.

While Malcolm X finally emerged from prison and became a spearhead for the civil rights movement, MacNolia, this collection reminds us, emerged from a promising youth but wound up a housekeeper. Jordan circumvents the melancholy of this arc by telling MacNolia’s life story in reverse. The book opens with her death in 1976, then cycles back to the '40s, when she met her husband. Some poems speak in the voice of MacNolia, while others adopt the voice of her husband, John.

Bouncing from one to the other, Jordan beats out a call and response rhythm. Here is John: “nicked skin, I spill blood / now to show the life in me. / dance, cry, glance, crawl, starve, / tongue, flesh, swarm, trap—girl, see: men / don’t need no big words to beg.”

Jordan casts MacNolia’s response to this overweening desire in a prose poem: “He couldn’t tell me from his mother; he couldn’t tell me from his sister; he couldn’t tell me from the last woman he had before me, and why should he—we’re all the same woman.”

In fitting with MacNolia’s skill and the theme of language, several of the poems in this collection unfold like definitions, building from one word the way a jazz solo can be built from a single note played against several bars. More often than not, the drumbeat here is John’s infidelity.

Occasionally, this gambit feels like a gimmick, drawing our attention to the poet’s clever structure rather than his sad subject. Kevin Young encountered this problem in To Repel Ghosts, his book of blues poems about painter Jean-Michel Basquiat. Young figured out how to modulate the importance of form in his most recent books, especially this year’s Black Maria.

It seems likely Jordan will do the same. After all, when he focuses on simply telling us MacNolia’s story, Jordan’s lyrics sing with a sweet and awful beauty, just like the blues. “My name must taste like a misspelled word,” says his MacNolia in “N-e-m-e-s-i-s Blues.” “But when it’s all over, I’ll show 'em how trouble gets stirred.”

If only that had been the case.