At the age of 10, Orringer learned that her mother had breast cancer. She breached into womanhood in a house filled with struggle and pain, yet also seared with tenderness. Orringer seems to have channeled much of that trying experience into her collection of short stories, How to Breathe Underwater.

Teetering between beauty and despair—and sometimes forcing us to question whether there is a difference between the two—her first book grapples with life in a world of cancer and dark water, bullets and sex; and often leads us to places where the light and sinister sides of human nature become indistinguishable. She melds the two forces with surprising skill, at times leaving us waxen with heartache, at others leaving us with nothing more than an impending sense of honesty.

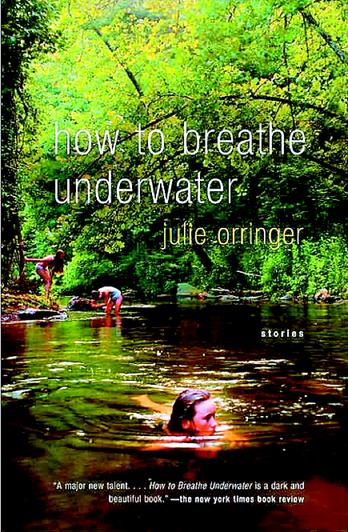

All nine of Orringer's stories wrestle with young women who are stuck somewhere between adolescence and adulthood and are not quite sure how to survive in their emerging worlds. Hence the title, How to Breathe Underwater, is the overarching theme of the book, symbolizing a condition that we all find ourselves in at one time or another: figuring out how to get a grip when we're outside our element.

The collection starts off by jumping into the world of two children whose mother has been diagnosed with cancer. (It's fairly easy to see where she gets her inspiration.) The story unfolds as the struggling family attends a support group dinner party one evening, where reality begins to blur haphazardly with unfettered emotion. While the adults of the party are off meditating in a far corner of the hosts' house, the children become trapped in an odd game of life and death with the other soon-to-be-motherless kids. This story is certainly about tragedy—creepy tragedy at that—and ends in a random twist of fate that almost leaves one wondering why we ventured to read the book in the first place.

But not all of Orringer's stories are so fatalistic. In “When She Is Old and I Am Famous,” we are taken for a ride through the somewhat merrier, although unabashedly cynical, eyes of Mira, a young woman vacationing in Florence with body image problems. She is ever-the-more intimidated by her freakishly beautiful cousin Aïda (“Ai-ee-duh: two cries of pain and one of stupidity”), who achieves the ideal fashion model body after a bizarre skewering accident causes her to lose a lot of weight.

In the least calamitous of Orringer's stories, “Note to Sixth-Grade Self,” the text stems entirely from inside the mind of an aptly aged little girl. There is still tragedy here, but only the kind of tragedy that a sixth-grader would classify as such (i.e. unrequited preteen love). Perhaps the biggest tragedy, in fact, is the lack of self-assurance that accompanies our early years, which becomes so apparent in the young girl's self-corrective thoughts, although it is etched with comedy: “When Miss Maggie comes out, do not look at her enormous breasts. Breasts like those will never grow on your scarecrow body. Do not waste your time wanting them.”

This is a bittersweet book. Orringer's writing is redolent with the strange and grotesque, but even her darkest stories are laced with humor and wit—a fusion that makes the sometimes heartbreaking prose worth the read. It's the kind of book that leaves you feeling uncomfortably satisfied. And just a little confused.