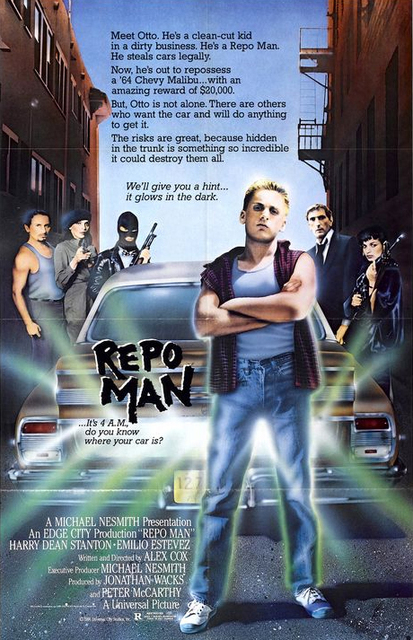

Bursting out of the streets of Liverpool and onto the avenues of Los Angeles, filmmaker Alex Cox made a resonant cultural impact with 1984’s Repo Man. At the time, Universal Pictures didn’t understand the satyrical punk rock comedy; but it became a major cult hit on the burgeoning home video market anyway. Cox followed it up with 1986’s music industry biopic Sid & Nancy. A string of increasingly cultish films ( Straight to Hell, Walker, Highway Patrolman, Searchers 2.0 ) trickled out in slow but steady succession.These days, Cox seems to be in a nostalgic mood. In 2009, he directed the “don’t call it a sequel” sequel Repo Chick. He’s spent much of 2010 completely “remixing” his 1987 punk rock spaghetti Western Straight to Hell, starring musicians Joe Strummer, Courtney Love and The Pogues. Now, Cox is touring the country screening his new cut of Straight to Hell Returns . He’ll hit Albuquerque’s Guild Cinema on Friday night. Luckily, we were able to chat with the surprisingly down-to-earth filmmaker before he hopped on a plane from Los Angeles. Repo Chick, Straight To Hell Returns : What’s brought on this sudden nostalgia in you? I looked at the old material because I thought that maybe we should be making it available for download. [ Straight to Hell ] was all broken up in 15-minute segments on YouTube. Maybe we should do a proper download. I was thinking that, so I was looking at the original DVD and [also] thinking, You know I wish that when we made the film we had access to the digital technology of today. We could have made it much crazier and much more extreme. Of course, we do now have access to the digital technology of today. So it’s just a question, then, of persuading my collaborators to participate in it. And that it would be lots of fun. All the new special effects stuff that went in came from these guys Collateral Image in Berkeley, who did bullet hits and blood and flames coming out the ends of guns. Another guy called Webster Colcord made stop-motion animation of skeletons. [Actor] Miguel Sandoval wanted to have a shot of his feet in the film, so we had to buy these special clogs that Miguel had chosen. Actually, Miguel bought the clogs. He paid for them. Then we had to shoot his feet, nails falling all around them in the hardware store. So it was a ton of stuff to be done in order for it to achieve its potential. I’m excited about seeing this new version. You haven’t seen it yet? It’s better. Oh, it’s better. The color aspect is really interesting. The audio is changed. In a lot of ways, it’s much more close to the film it should have been. What attracted you to doing a punk rock spaghetti Western in the first place? Well, it was only by accident, really. We’d been trying to go on a tour of Nicaragua, a rock and roll tour with [Joe] Strummer and The Pogues. They had agreed to set aside a month of their busy schedules so we could do that. Then we couldn’t raise the money for the tour. So the [eventual] producer of the film, Eric Fellner, said, “You know, I think that I could raise the money for a film—if you could come up with a script that could be shot for a million dollars.” Strummer used to go down to Almería in the south of Spain for his holidays with his family. So he had already seen these movie sets and the desert there and loved it. I said, OK, we’ll go [there] and make an Italian Western. That’s how it came about. Just because of the quick-wittedness of the producer being able to turn it around from a musical tour to a feature film. But you were already a fan of Sergio Leone and the other Italian filmmakers of the ’60s. Big fan of spaghetti Western. I love spaghetti Westerns. Did that make it intimidating? No. Because the thing is, it’s all just stuff , isn’t it? I think one just wants to have fun , really. It’s nice to be able to do things that you enjoy. And it’s nice to be in a place that’s really unique. Those desert locations in the south of Spain really were something. They were very beautiful and very quiet and very pure. It was really quite a wonderful experience going there and living there for a little while and shooting those locations. Everybody was really quite moved by it in a funny way. Maybe because it was years later and we were aware that Henry Fonda and Jason Robards and Klaus Kinski had trod here. Having finished this new cut of the film, what made you decide to tour with it? To make more people see it! [ Laughs. ] Because in theory, if the director shows up or one of the actors, then more people come to the screening. It creates a bigger buzz. Then, eventually, when the thing is available for download or DVD, more units are moved . So there’s that. But it’s good, in a way, since there isn’t really alternative distribution anymore. There used to be with Roger Corman and Samuel Arkoff. This is really what an independent filmmaker most desires, is just just to see the film play in the theaters. Do you still think of films that way? Everybody wonders what the future of distribution will look like, but to me seeing a film in a theater is something special. I think so too. But then I have this idea in my head: Oh yeah, I’m in a big theater with all these people, all having a communal experience, blah, blah, blah. But really, a lot of the time when I went to the pictures—even when I was a kid—these were obscure films. Like Sergio Corbucci’s … whatever. There weren’t a lot of people. I could be sitting in the cinema at two o’clock in the afternoon watching one of these films and having it almost to myself. So I’m not so sure that the cinema for me was a communal experience. … Unless it was going to see 2001 at the Cinerama Dome. That sounds all right. That was pretty impressive. You’ve always been an independent filmmaker. However, with your most recent films [ Searchers 2.0, Repo Chick ], you’ve made a turn toward ultra-low-budget microcinema. Yeah. I think it’s very interesting, given the technology is so readily available now. The ability to do special effects and treat things and change color and everything. You can make a very slick-looking film without a great deal of money. That’s encouraging. I see so many directors who started out in independent cinema, then went to Hollywood. I would love to see those directors back at their roots trying to work with as little as possible. I guess they see that as a step backward. But it seems to me like a real artistic challenge. I think so too. But I don’t think a lot of people are in the film business for the artistic challenge. I think it’s more like a lifestyle choice. It can be very highly paid if you’re successful at it. Then you have a sort of obligation to maintain that lifestyle and all that that entails: what you have to do, who you associate with, how old your wife is, what kind of pet you have. All these issues. It becomes something other than the art of film. I think my big failing has always been to think of film as an art form. As opposed to remembering that it’s a business where you’re supposed to make money. A couple nights before you’re appearing at the Guild Cinema, we had Zack Carlson and Bryan Connolly there signing copies of their book Destroy All Movies!!! The Complete Guide to Punks on Film. Which brings up a point you seem uniquely qualified to answer: Is punk rock a genre of film as it is in music? [ Long, thoughtful pause. ] I don’t know. I think it’s a bit like what became of punk—which is, essentially, it just became a fashion thing. Whatever was interesting about the politics of it just seemed to sort of get left behind and fade away. But there were these bondage fashions and haircuts and all that stuff that remained. You could say that, superficially, Blade Runner is a punky looking film. But it doesn’t really have a punk aesthetic. But some of your films ( Sid & Nancy ), some of Derek Jarman’s ( Jubilee ) or Julien Temple’s films ( The Great Rock ‘n’ Roll Swindle ) come to mind. I would think that something like [Temple’s] Absolute Beginners has certainly got a punky attitude, hasn’t it? It’s kind of a fresh, streetwise thing. You could say the same about Repo Man or Sid & Nancy because they’re in that world. In a way, what was interesting about punk was what went away—the political aspect. That’s what Buñuel said interested him about surrealism. It wasn’t just that surrealism was a way of selling paintings to wealthy Texas collectors—what it became for Magritte and Dalí—but it was actually a revolutionary movement that was supposed to bring down society as we know it. And in that sense, it completely failed. Do you think there are people out there picking up that political flag? Oh, I think that there is, in a certain way, a common thread that runs through the punks, the surrealists, the green movement, the pacifist movement, the animal rights movement. I think there’s all kinds of cases of people thinking outside the box or living outside the box. Do you get see much indie cinema that gives you hope these days? I think that [Dylan Avery’s 9/11 conspiracy documentary] Loose Change is very good. I’ve seen three different versions of Loose Change now and I find it fascinating. I also find it fascinating how it was getting out. It was handed out for a long time. I’d see people handing it across the counter in bars. They were literally passing it around. Now it’s got a download site and real distribution and stuff, so maybe that takes away the kind of weird edge that it had. But Loose Change is very interesting. It should be widely seen. What about your future? Do you see yourself funding and self-distributing more microcinema? No. My wife won’t let me. She says that’s the last time. I can’t spend any more of my money on films ever. Not even if you shoot them in the back yard? Well, if I’m making a film about the dogs, which doesn’t cost anything. … That’s also what the guy at the Venice Film Festival said. The last film I showed [was] at the Venice Film Festival. The head of the festival, this guy Marco Müller—he speaks like 17 languages, he’s incredibly urbane and intelligent, well-dressed—he sees me. It’s the night of our screening, we’re all coming up the red carpet—we’re this shambolic gang, no limo or anything—and he goes, “Alex, you can’t make any more cheap films. You just can’t do it. Stop now.” [ Laughs heartily. ]

Alex Cox at Alibi Midnight Movie Madness

Two screenings (10 p.m. and midnight) of

Straight to Hell Returns . Cox will be at the theater in person to talk about the film and participate in an audience Q and A. Friday, Nov. 12 Guild Cinema 3405 Central NESee also this interview with Alex Cox on Straight to Hell Returns