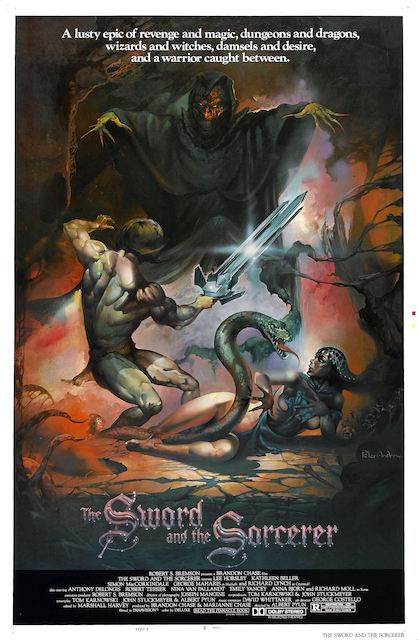

Writer-director Albert Pyun may not be a household name, but his films took up a sizable chunk of real estate in video stores throughout the ’80s and ’90s. Look up his resume and you’ll find nearly 50 films—just about all in the low-budget, direct-to-video realm. Starting with his first feature, 1982’s late-night cable TV staple The Sword and The Sorcerer, Pyun established himself as one of the B-movie kings of Hollywood. Titles like Radioactive Dreams, Vicious Lips, Alien From L.A., Cyborg, Bloodmatch, Dollman, Brain Smasher… A Love Story, Arcade, Kickboxer 2: The Road Back, Nemesis and Omega Doom are sure to conjure up fond memories for those of us who grew up with a stack of VHS tapes next to the television.In 2008 Pyun began work on his dream project, an unofficial sequel to Walter Hill’s 1984 urban fantasy cult film Streets of Fire. Pyun’s continuation, Road to Hell, features two of the first film’s stars (Michael Paré and Deborah Van Valkenburgh) and a handful of the original tunes penned by composer Jim Steinman. Pyun is now touring the country with the film and will make a special appearance at Albuquerque’s Guild Cinema on Saturday, Aug. 17. (Trivia note: Two of Pyun’s films were shot New Mexico: 1994’s Kickboxer 4: The Aggressor and 1996’s Raven Hawk.) Alibi grabbed the chance to gab with Pyun from his home in Los Angeles.I came of age during the Golden Age of home video, when you could walk into your neighborhood video store and see 100 new films on a weekly basis. What was it like for a filmmaker working during such a fertile period?Actually my career started in the late ’70s/early ’80s when it was still just an all-theatrical world. Your film had to be able to make money in theaters or drive-ins or you couldn’t get the film made. That’s where I started with The Sword and the Sorcerer and Radioactive Dreams. Then, around that time in the early ’80s, cable TV was coming in. That created a secondary market for the films, and it actually became easier to get films made. Then home video really kicked in in the mid-’80s. The amazing thing about that was a lot of the studios, once they realized there was a giant pipeline out to everywhere, they made all these deals based on “We’ll deliver you 30 titles this year, or 50 titles.” And the video stores and the video distributors really needed that. They were still in their infancy. There wasn’t that much product circulating around, so they really needed every week for a lot of stuff to be coming out. And so I found myself in the position where a lot of these studios, like Cannon Films, had made a deal where they would deliver, like, 50 movies in a year. But the truth of it is a lot of their films, for various reasons, ended up costing way too much money. So they end up taking money away from a lot of the films they were supposed to deliver to put onto these larger budgeted movies. That created a weird situation that I dropped into, which is they would come to me and say, “Look we need to deliver this film or this film or this film. It can be anything you want it to be, but it can only cost this much money because that’s all we have left.” I guess I got freedom to do some pretty weird movies, but at the same time the conditions were [that] all the money had already been spent by Cannon on Superman [IV: The Quest for Peace] or Runaway Train or whatever. So I got to make movies, but not with very much money.After Cannon Films you worked for Full Moon, a major direct-to-video distributor. How were the companies similar or different?The companies were essentially the same, except that at Full Moon, [owner] Charlie Band really had more to say on every movie that was made. He still didn’t provide any more money. … He and I didn’t actually get along that well. We had a lot of conflict about this because my feeling was if I was gonna make a film for him for no money and not get paid, then I wanted to make the film that I wanted to make. And a lot of the time, they weren’t films that fit in with the Full Moon style and content.Can you give me an example?Well on Dollman, [Band] originally said, “I need to make this movie called Dollman about this scientist whose experiment goes wrong at home and he shrinks down and has to fight insects and stuff to get through the day before his size returns to him.” I went, well I think I’ve seen that movie before. And for no money, it’s just not very interesting because it will look cheesy. I said instead what I’d rather do is make a movie about a Dirty Harry [-type character] who is only 13-inches tall, from another planet and ends up in the worst place on Earth—which at the time was the South Bronx. Then he’d have to do his Dirty Harry act in this very hostile environment. I just thought that was a much more interesting juxtaposition of the small human in a larger world. It was much more violent and deviated away from the more PG-rated Full Moon stuff. Luckily [Band] went for it, but in the end he took the film away and re-edited it. Same for Arcade, which was a film we did around the same time. Except that on that one I brought in David Goyer to write. [Band] really loved David Goyer’s writing. David Goyer, of course, went on to do The Dark Knight, Man of Steel—so he was obviously very talented. David was in his early 20s [at the time], and we came up with this idea. Originally Charlie had an idea of what he wanted this Arcade movie to be. David and I came up with a different, much darker idea. Again there was a conflict, but Charles so loved the writing that David did in the script that he was more accommodating. Except that he never really came up with the money to produce the CG effects that that film required. It sat on a shelf for a while. That was another film where it got taken away, and I wasn’t involved in editing.Was it typical of the time—that you weren’t involved in post-production?It started really with Cyborg, when Cannon took the film over and gave it to [Jean-Claude] Van Damme to edit. That was the theatrical release version of the movie. At that time that started a trend where the next, Captain America, was taken away by the studio and recut. Virtually every movie, the next 12 or 13—up until the time I did a film called Adrenaline for Miramax, and Bob Weinstein took that over and re-edited the film. That was kind of the straw that broke the camel’s back. After that I said, I’m not doing any more films for anybody who’s gonna have a chance to take the film away from me. From that point on, I started doing my own films and doing my own financing, my own distribution. Between Menahem Golan at Cannon, Charles Band at Full Moon and Harvey Weinstein at Miramax, you’ve worked with some of the most notoriously tightfisted, controlling producers in Hollywood.Oh yeah. And actually, Kickboxer 2 was done for a company called King’s Road. A gentleman named Steve Friedman owns King’s Road, and he was a very strong-willed owner as well. Because the first film that he ever produced was The Last Picture Show. He won Oscars for that. So in his mind, his way of doing things and his knowledge had real validity. He was a little difficult. A lot of people didn’t like working with Steve. I was the only director, I believe, who made more than one movie with him. … His style was very confrontational and autocratic. I had already been so used to that, having fought with Charles Band and Cannon and stuff. So when I worked with [Friedman], it just sort of rolled over me.The 1990 version of Captain America came in well ahead of today’s superhero movie curve, but the film is notorious in the realm of budget failures. How did it start out?I read the script when it was still at Cannon, and I thought it was great. I told Menahem [Golan], when he left to form his new company 21st Century, that this was a project he really needed to bring with him. Because it could be something special and a good start for his company. Like any new company, funds are tight. He wanted to make the film because the option was going to run out on it, and he didn’t have the money to re-up the option. So he said, “What can we do? Can we go make this for a budget?” I said, well I think we can do it for, like, 6 million. We went to London and he talked to the bank and I did a presentation and the bank said, “OK, we’ll do it.” It looked like we had the funding, so we went ahead and took the movie to prep. When we got on location, it turned out the money had disappeared. The bank loan never closed and the bank pulled out. There was never any money to complete the film. I even shot a day where I had no film, but I shot the day anyway because I didn’t want anybody [knowing] that we had run out of film. It was really tough. All the action, naturally, got thrown out of the script. The film got smaller and smaller—which I didn’t think was that bad at the time. I thought that really the story of Captain America, what made it interesting, what I liked so much about it growing up, was the story of Steve Rogers and what happens to him. And what price he pays to become Captain America. And the expectations that are put on him. I thought we did a decent job of bringing that story to the screen. But when we got done, the first screening that Menahem had of the film for Columbia-TriStar, they just went, “Where’s the action? This is like a drama. We want the action.” And there wasn’t any because we hadn’t shot any. So there started being bad word of mouth about the movie. That got out. They tried to re-edit it to make it seem more like an action movie. But that just made it worse. It made it more chaotic and nonsensical. It hasn’t been until the last two years that my version, the director’s cut, has gotten out. The film has really gained a following since 2010, with the new Captain America being made. The interest really came back. I had screenings of my director’s cut in Las Vegas and Austin and sold out—600-700 people, huge lines outside at midnight shows.What did you think when you saw Captain America: The First Avenger?I was just amazed at how much CG—which I didn’t have access to at the time—really does help the story. And then I had a lot of fights with Marvel making the 1990 version. They were so restrictive as to what I could and could not do with the character. I was shocked that in [the 2011] version, [Marvel] allowed that film to do a lot of the things that I had requested in the 1990 version that they had said no to: adjustments to the costume, the look, the color. Captain America’s shooting a gun. I asked if we could do some weapons stuff in the 1990 version because we couldn’t do all the big action. They said no, you have to stick with the shield.So what led you down the Road to Hell? I saw a film in 1984 that I just thought was the greatest movie I’d ever seen in my life, and that was Streets of Fire by Walter Hill. I really thought that movie was gonna change cinema forever—the way it changed me. I saw it at an early screening at Universal before it had been released. I came running back to the editing room where I was editing Radioactive Dreams. The only other editing being done in those bungalows was Salvador by Oliver Stone. In that time I got some understanding about being courageous with the medium and trying to do different things and not thinking of film as a job or paycheck or for fame and fortune, but as an art. I could hear Oliver Stone every once in a while [through the walls] shouting about being unconventional and not trying to do the same thing. Seeing Streets of Fire really seemed to encompass all that. The new film language, the way Freeman Davies edited the film, the way the film was shot: Everything about it was different. It smashed together different genres. I just thought that was the kind of movie I wanted to do, if I had the opportunity to keep making movies.So do you look at Road to Hell as an official sequel or more of a “spiritual” sequel?It’s more of an homage. Because 28 years have passed since then. It’s really a movie about what would happen to a character like Tom Cody [Michael Paré] after Streets of Fire. In the end you see him riding off in the car and think he’s off on this great adventure. But what happens if life doesn’t turn out so well over the next three decades—as it has for most people? Especially if you’re a soldier and you earn your living fighting and shooting guns. Eventually that has to catch up with you, and you realize you’ve given up everything—family, love—for this lifestyle that now has eroded your soul a little bit. This film is really about somebody like that—an iconic hero trying to come to peace with the choices that he made and what he’d given up to have that.What made you want to go out on tour with this film?I never really went to film festivals or went that whole direction with most of my career. I was usually on to the next film and generally out of the states on foreign locations making movie after movie. So I never really followed what happened to the movies after I finished them. Because I never really worked on the editing on any of them, you just lose track. You have to detach emotionally from the film. Because of that, I didn’t understand how films have fans and those fans would eventually go to film festivals. And there was a lot more of them than I ever imagined. I only saw the negative stuff because negative stuff was generally what was thrown in my face. My experiences with the heads of a lot of studios was so negative that you feel everything about the film and the work that you did was unappreciated and not liked. So I kinda went through that. Then, in the early 2000s, I started getting invites to film festivals to get lifetime achievement awards. I went wow, wait a minute, I’m gonna get an award for a body of my films? I went to these countries like Spain, the Netherlands. … I went to Brussels a couple years ago, and I found out that Radioactive Dreams had actually won the best film of the festival in 1986—which I never even knew about! I started realizing getting into that world through the Internet, that the films had a much bigger fanbase and affected a lot more people than I had ever dreamed of. So now I take pleasure in screening the film and being with the people as they experience the movie, so I can be there viscerally. That’s been wonderful.

Road to Hell screeningSaturday, Aug. 17, at 10:30 p.m.Guild Cinema (3405 Central NE)Tickets: $10Director Albert Pyun will participate in a post-film Q&A