Film Interview: Riding To Recognition In Indian Horse

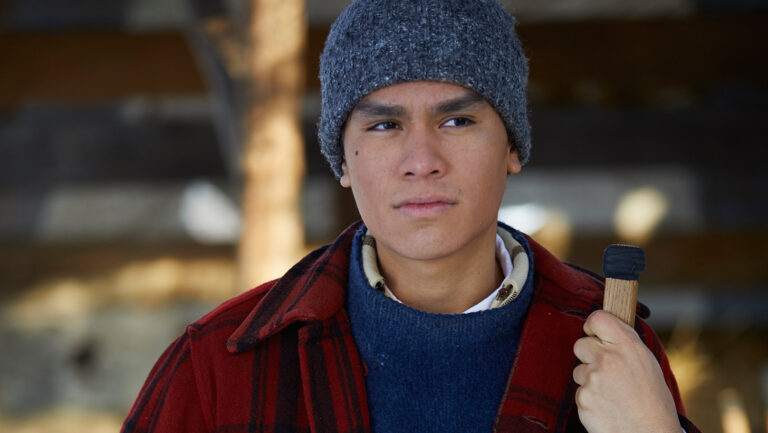

An Interview With New Mexican Actor Forrest Goodluck

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992