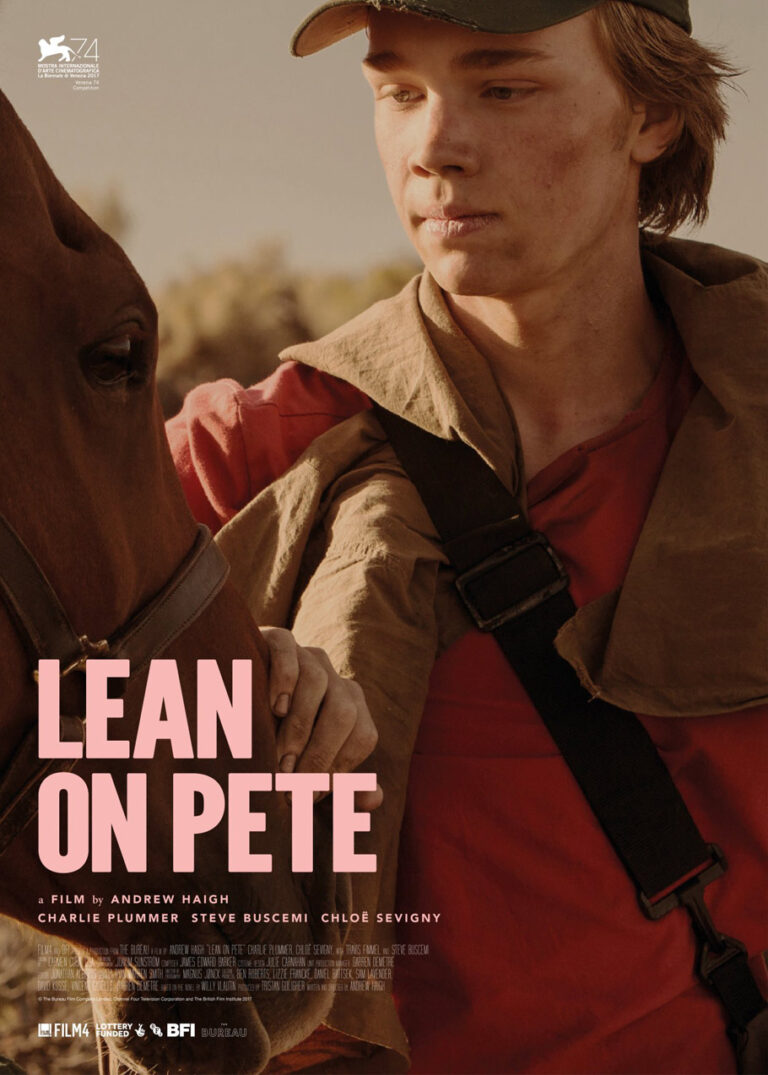

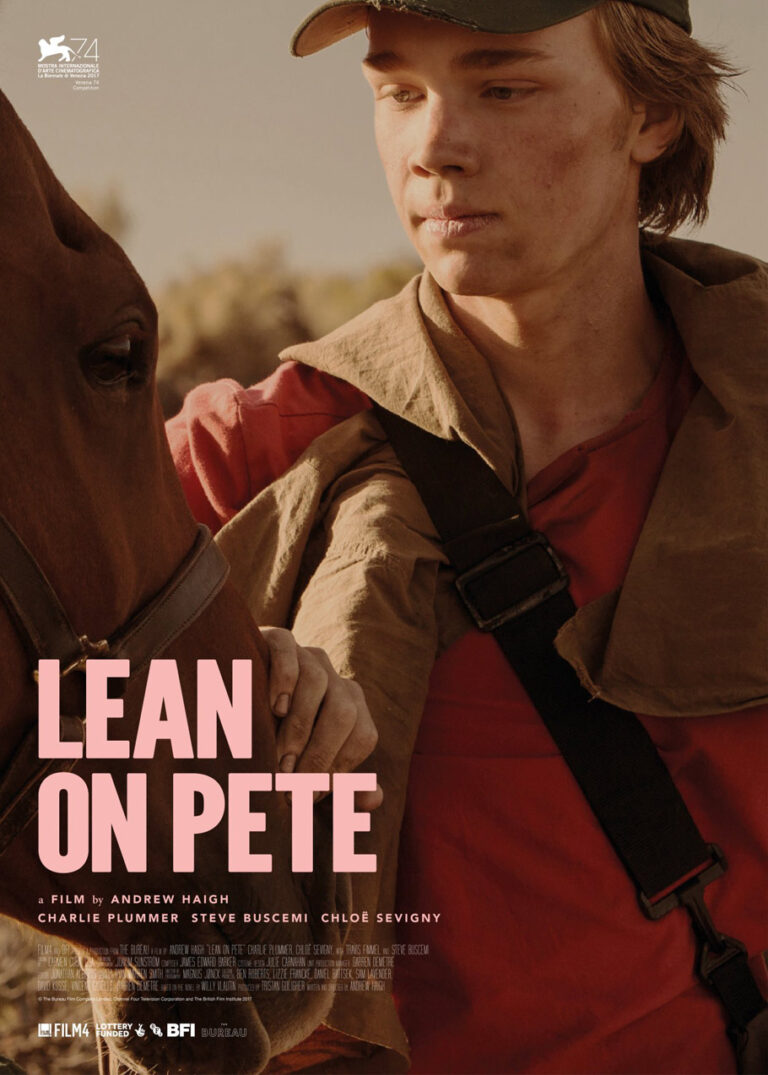

Film Interview: What Would Willy Do?

An Interview With Novelist, Musician Willy Vlautin

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992