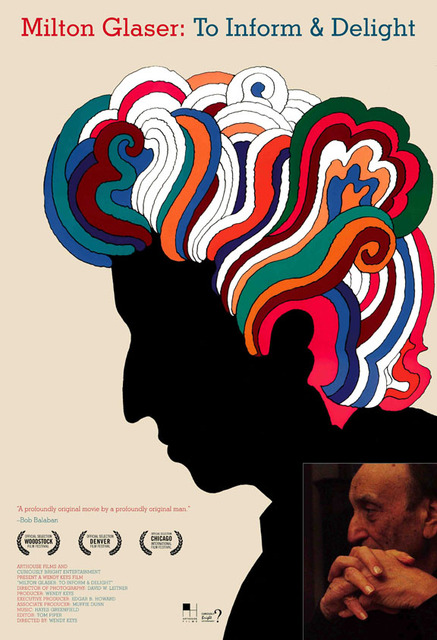

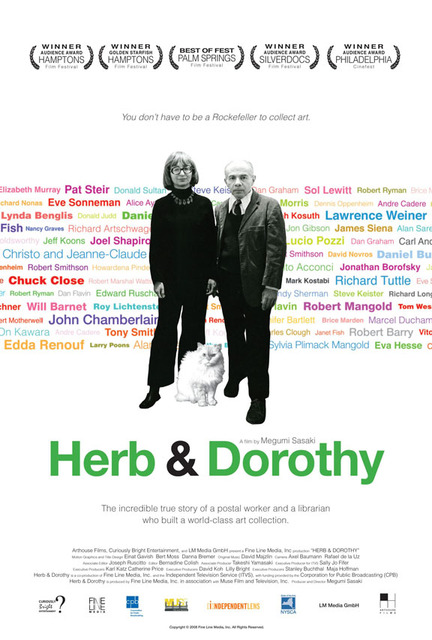

When one man’s wadded-up piece of paper is another man’s exhibit at the National Gallery of Art, the infinite mystery—and absurdity, perhaps—of the art world is clearly evident. Two documentaries dealing with people who penetrated, comprehended and conquered the often confusing realm of aesthetics take an artful, layman-friendly look at differentiating between what is visually ordinary and what is extraordinary.Film No. 1, Milton Glaser: To Inform & Delight , was released in April and is making the rounds at art-house theaters across America. The documentary is a biography of Milton Glaser, a boy from the Bronx who became one of the world’s most well-known and influential graphic designers. Most notably, Glaser is responsible for the persisting “I ❤ New York” campaign and is co-founder of New York Magazine . He created the 1967 Bob Dylan poster featuring the singer’s silhouette with serpentine tendrils of multicolored hair (used in the doc’s movie poster). He made logos for DC Comics and designed countless other things ranging from book jackets to large-scale murals to grocery store layouts. His work is extremely diverse, containing a breadth of styles and levels of complexity. It tends toward playfulness, with reoccurring visual puns, and interacts with its audience in an articulate way.Film No. 2, Herb & Dorothy , was released last year. It concerns legendary couple Herb and Dorothy Vogel, art lovers and one-time amateur artists who in the ’50s began to collect and fill their tiny rent-controlled Manhattan apartment with modern art. Dorothy, a librarian, paid the bills, while the entirety of Herb’s postal clerk salary was devoted to the purchase of work by emerging artists. Through decades of meeting and befriending the likes of Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Will Barnet, Robert Mangold and Richard Tuttle—while also diligently attending nearly every New York City art function—the Vogels managed to amass a world-class art collection worth millions. Much of these works take a Marcel Duchamp approach, the artist having grabbed whatever material was lying around, given it a name and called it a work of art.The obsessed collectors, in their cramped apartment packed to the gills with some of the most incomprehensible art on Earth, clearly see its worth. Whether it’s a pile of bricks, a tiny piece of rope nailed to the wall or a mass of wire, the Vogels speak that visual language. Meanwhile, over in Glaser’s world, he proclaims art is what society determines it to be at any moment.The difference between these two stories is postmodernism versus modernism, and how the forms communicate with their audiences. Glaser’s postmodern work is easy to understand. With it, he aims to translate a shared feeling or create commonality among people. The work the Vogels collected doesn’t necessarily fail in that respect—it’s just that, aside from it being private art rather than public art, the function is obscure and the overall meaning tends to confuse. One is clear, the other sometimes seems to be total bullshit.Art form versus art form aside, both films do solid jobs of telling excellent stories about people who spent their lives dealing with the mysterious nature of artistic taste. Milton, Herb and Dorothy are all interesting and endearing … but I’d rather get a drink with Milton.

Milton Glaser: To Inform & Delight