Take, for example, writer/director Robert Towne's long-brewing adaptation of Ask the Dust. The filmmaker apparently stumbled across John Fante's cult novel while researching Los Angeles history for his legendary Chinatown script. Captivated by Fante's gritty depiction of Hollywood's early days, Towne set about crafting a big screen adaptation. Now, 30 years later, he has succeeded. Such as it is.

The film's recreation of early-'30s L.A. is rendered in the sort of detail that can only be described as “loving.” The film (actually shot in South Africa) begins with a computer-generated helicopter shot, sweeping down from the Hollywood Hills and into L.A.'s long-gone Bunker Hill neighborhood with its dingy residence hotels, its soot-blackened palm trees and its famed Angels Flight funicular railway (dismantled in 1969).

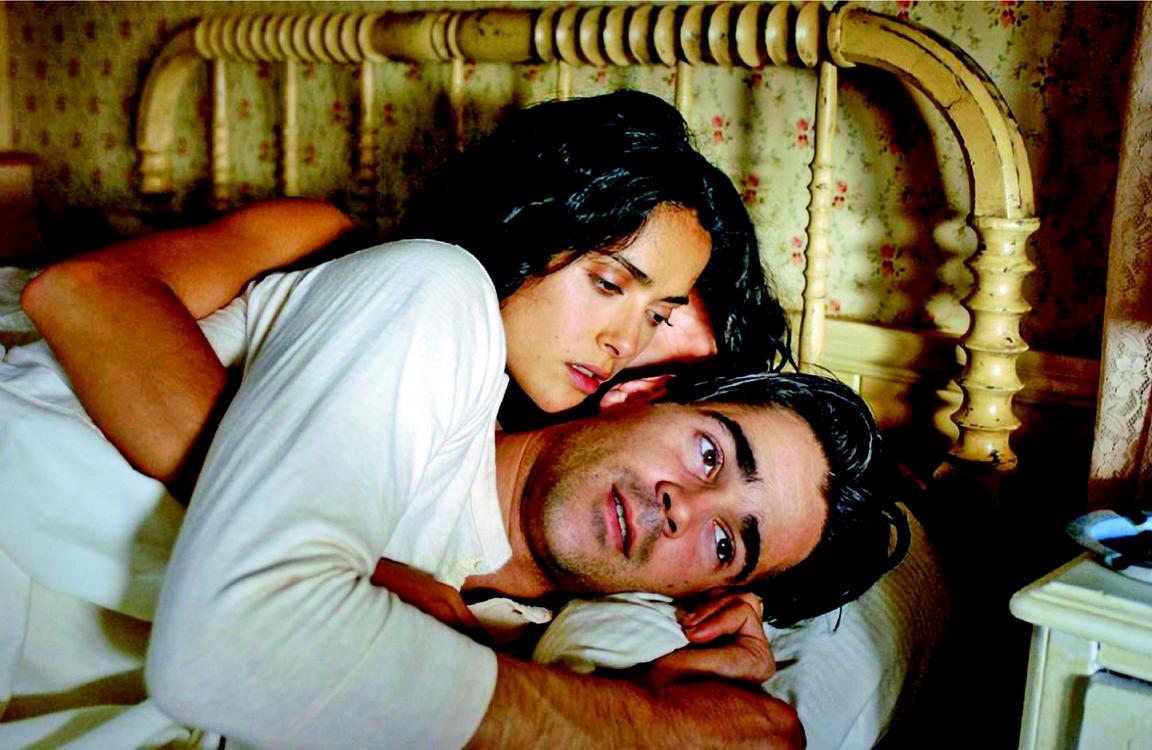

In this seedy, Depression-era world we are introduced to Arturo Bandini (Colin Farrell, bravely fighting off his accent). Having published a story in H.L. Mencken's literary magazine, the cocksure Bandini has come to L.A. to write the Great American Novel. Unfortunately, several months after his arrival, he's struggling with writer's block and subsisting on cigarettes and oranges (at the time, L.A. was still riddled with orange groves).

Here, then, is our first sign of trouble. It's not hard to see what attracted Towne to this tale of a struggling writer searching for his inner passion. But, if past films have taught us anything, it's that writers rarely make good subjects for cinema. There have been a few notable exceptions (1996's The Whole Wide World, 2002's Adaptation, last year's Capote). For the most part, however, writers don't make the most visual or active of protagonists. Their job is primarily to sit in front of a typewriter and think a whole lot.

Things pick up slightly when Arturo resolves to spend his last nickel (literally) in a local watering hole. There, he crosses paths with a stunning Mexican waitress named Camilla (Salma Hayek). Arturo is instantly smitten with Camilla and vice versa. But for some inexplicable reason, the two spend almost the entire movie squabbling like schoolchildren. Racial epithets are hurled, manhoods are questioned and tempers are lost. Honestly, the behavior is vexing; it makes our lead characters come across as infantile and totally indecisive.

Arturo, despite the fact that he looks like Colin Farrell, is supposed to be a naïf in the ways of womanhood–hence, his writer's block when it comes to the Great American Novel. Camilla, on the other hand, is billed as a “fiery Mexican,” which tells you pretty much all you need to know about her character. Shortly after their first meeting, Arturo and Camilla end up skinny-dipping in the Pacific Ocean. As most filmgoers know, Farrell and Hayek look pretty damn good without clothes on. Unfortunately, a nude romp doesn't do much to cement their sexual attraction, and they continue to fight with one another. Talk about a cold shower.

The film proceeds episodically, failing to build up much dramatic tension. This sort of literary portrait of people and place plays out well on the page, but fails to come alive on the screen. A romantic subplot about a troubled Jewish girl (Idina Menzel, fresh off Rent) gives the film its most interesting moments, for example, but soon it's back to more of Farrell and Hayek.

Eventually, the two hook up, and the story descends into unforgivable melodrama. There are a few brief nods to topics like racism and art, but the plot fails to grow organically out of character and is, instead, shaped by the external Hand of God (in the form of the patronal Mencken, the Long Beach earthquake of 1933 and an untimely illness).

Clearly, Towne envisioned a tough look at Depression-era dreamers–something along the lines of They Shoot Horses, Don't They? or The Day of the Locust. (Donald Sutherland, who starred in the 1975 adaptation of The Day of the Locust even drops by for a cameo as one of Arturo's burned-out neighbors.) Unfortunately, despite some great period recreation, it’s hard to connect to the people populating this historic (occasionally histrionic) version of Hollywood.