Like most tragedies, things started out well for Enron, got better and then so good that life seemed near perfect, until one day it all came crashing down. It's a timeworn theme stretching from Greek mythology to Humpty Dumpty. For that matter, Alex Gibney's new documentary Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room plays like a seamless tragedy built on fraud, deceit, suicide, hubris, complicity and every other personality trait we all wish didn't exist. Just don't expect the traditional retribution at the end. Then—we're talking about real-life corporate America here—you would be suffering from what Alan Greenspan calls “irrational exuberance.”

Based upon the book The Smartest Guys in the Room: The Amazing Rise and Scandalous Fall of Enron, Gibney bares plenty of facts, figures and news clips from congressional testimony to satisfy any newshound's interest. But the film's strength rests in its presentation of the amoral human condition at work, especially in the form of exclusive videotapes and audio recordings of Enron's energy trading practices and corporate philosophy.

Most folks know the basics about Enron. In less than a year, it went from being the nation's seventh largest company, valued at $70 billion, to bankrupt. When the ship sunk, it took 30,000 jobs with it, a $2 billion pension fund and the life savings of countless others. While employees lost everything, the hucksters responsible for the collapse cashed out in time to walk away with millions.

What makes this film a must-see, however, is not the rehashing of headlines, but the inside story of Enron executives who took credit for being the smartest guys in the room when the company was soaring but tried to skirt responsibility for its demise.

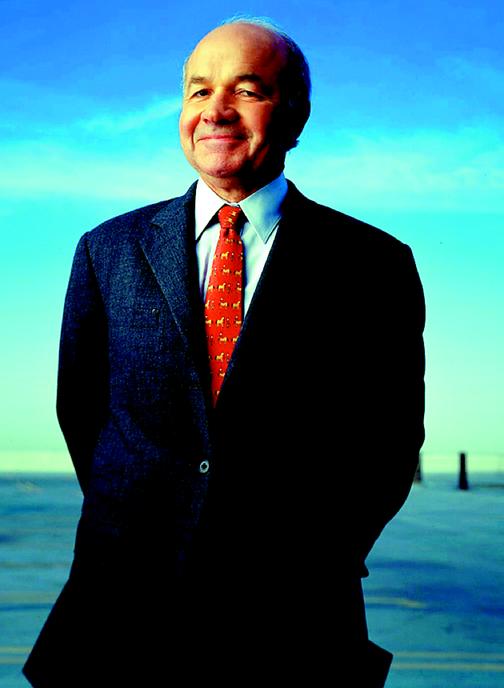

Company president and founder Kenneth Lay appears the most unrepentant of them all. He rose from humble beginnings and wrapped himself in the cloth of corporate integrity to become the poster child for free market success during the stock market bubble of the late '90s. By the time Enron filed bankruptcy in December 2001, though, it became clear that Lay and others falsified profits and made up one egregious lie after another to conceal the fact that the company was broke.

In this light, there are obvious lessons to learn from the film. For one—if it looks too good to be true, it is too good to be true. Secondly—diversify!

There are cynical lessons to learn as well, which Gibney explores without, thankfully, transforming his film into the kind of agitprop that's made Michael Moore a celebrity. For example, we learn the story of Lou Pai, a lesser-known Enron executive, who walked away with more than $350 million in stock sales when he left Enron in 2001. Pai apparently enjoyed the strip clubs more than reading spread sheets and one day abruptly quit the company, left his wife and split town with an impregnated concubine. Meanwhile, during the years he ran Enron Energy Services, the company subsidiary lost more than $1 billion. Shareholders got screwed, but Mr. Pai went on to become the second largest private land owner in Colorado, including the Culebra Peak (yes, the whole mountain).

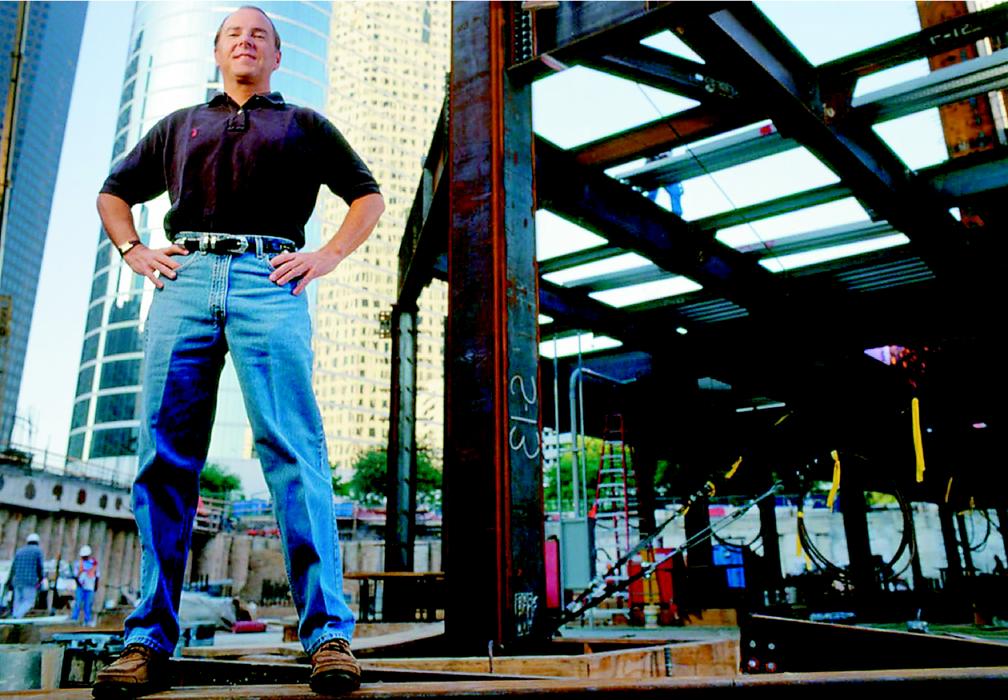

No tragedy is complete without a hero and that's Sherron Watkins, an Enron vice president who became known as the “whistleblower” in media-speak, but who was simply an honest and faithful employee. There is a priceless moment when Ms. Watkins offers her still awestruck assessment of the whole charade. She refers to Enron's CEO Jeffrey Skilling—who is described as “incandescently brilliant” but comes across in interviews as a humorless SOB that can't spout two sentences without squeezing a lie in between them—as an insincere cult leader. Skilling resigned from Enron in August 2001 after he cashed out nearly $60 million in stock options. Two months later, the company stock plummeted, and by December it was worthless. Ms. Watkins described the situation as “Jim Jones feeding us the Kool-Aid and deciding not to drink it himself.”

There is one last villainous aspect of the film that makes it essential viewing for anyone with faith in “private accounts.” The tragedy of Enron was not and never could be the exclusive work of a handful of executives. From California's rolling blackouts to Enron's Wall Street crash, some of our nation's most esteemed bankers, investors, lawyers, accountants and government regulators all facilitated the crimes by accepting the fraud as part of the American enterprise process. In the end, warns Watkins, “It can happen again.” Now that would be a hard lesson.