Film Review: Life Itself

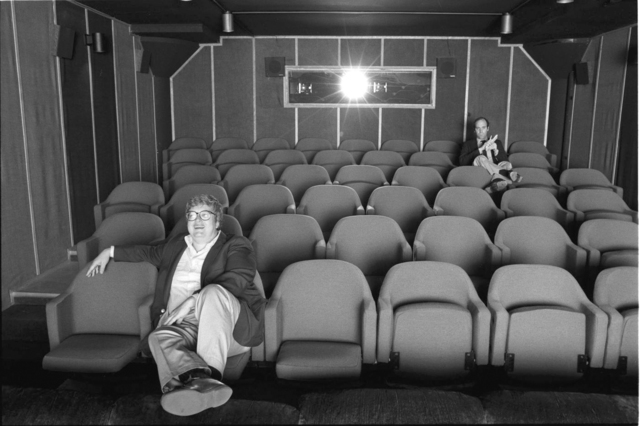

Poignant Documentary Points The Camera At The Life Of Movie Critic Roger Ebert

Whatever they’re watching

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992

Whatever they’re watching