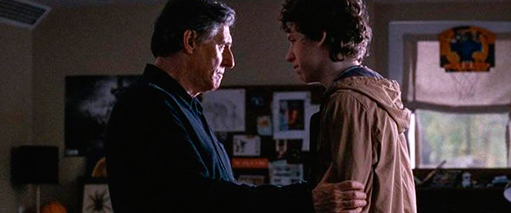

Film Review: Louder Than Bombs

Grief Drama Cripples Three Men With A Bad Case Of The Feels

son. Don’t let yourself go. Cause everybody cries. And everybody hurts. Sometimes. ... Sing it with me!”