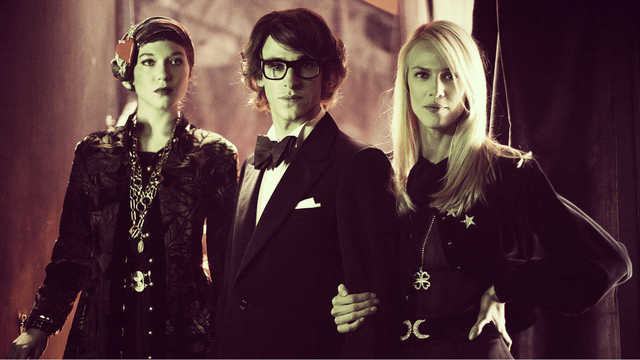

Film Review: Saint Laurent

French Biopic About Famed Fashion Designer Gives Us Glorious Surface, Poor Structure

baby!”

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992

baby!”