Film Review: The Salt Of The Earth

Breathtaking Photography Forms Backbone Of Life-Changing Biopic

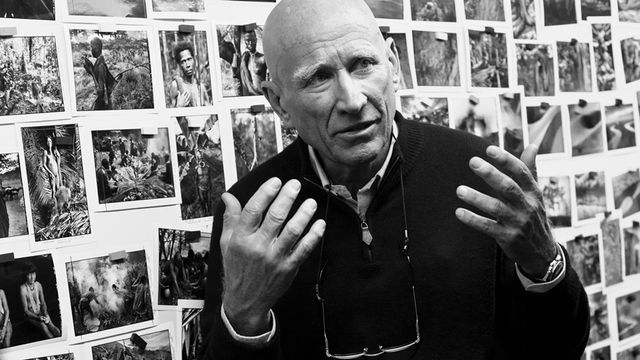

Salgado

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992

Salgado