Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence is writer/director Mamoru Oshii's unapologetically heady reworking of the first film's raw material into an incredible visual thesis. Where GITS was an action film with a complicated metaphysical plot, Innocence is a meditation on the nature of humanity and its technological extensions illustrated by eye-popping CGI work and explosive set pieces, a high-tech paean to alienation. Oshii even goes so far as to eliminate the most obvious fanboy draw, hardbody pinup gal Major Kusanagi, whose ghost alone makes an appearance this time around.

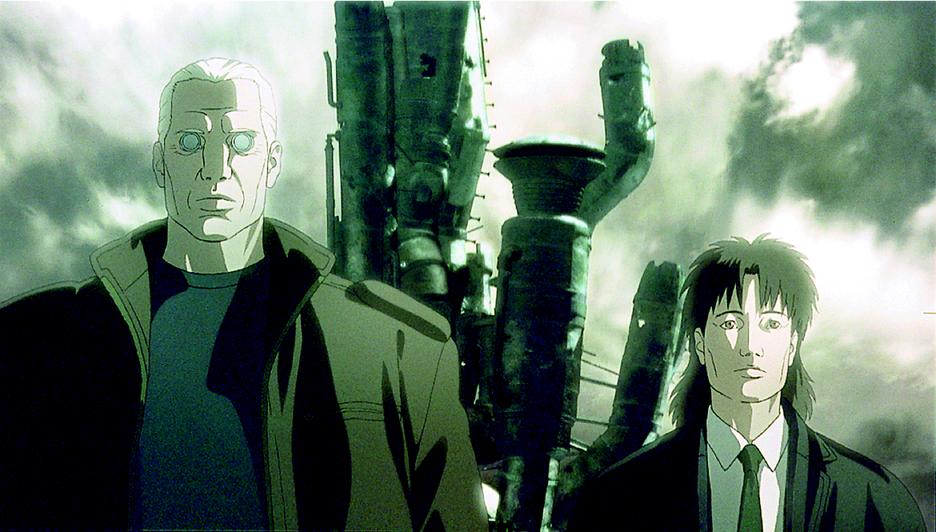

The bare plot of Innocence, while original to the film, would not be out of place in Masmune Shirow's T&A-infused source manga nor the new, more juvenile “GITS: Stand Alone Complex” TV series: A sinister megacorp's illicit prerelease sex-bot “gynoids” start brutally murdering their owners–but why? Our hero, the glum cyborg Batou, and his mostly-human partner Togusa step through police procedural paces to solve the mystery.

As with any good supercop movie, there is suspense, tension and violence (Batou's one-man-army takedown of a Yakuza stronghold being a particular standout). The difference here is that, as the film progresses, the procedural becomes more surreal and philosophical, until the who-done-it story line cross-dissolves into a dense intellectual discussion. Oshii doesn't care if it it “bogs down” the action or seems pretentious. The ideas take precedence, which is nothing if not refreshing. The dialogue, with its incessant quotations from Descartes, the Old Testament and Confucius would be ridiculous except that it is established that our augmented protagonists have “external memory” always accessible via some persistent high-tech wireless network for on-the-spot Googling. That such a constant, subliminal link to personal file servers might modify human interaction is a reasonable extrapolation. Dumber sci-fi fans might not dig it, but for them there's always The Phantom Menace.

In the final reel, when Batou and Togusa head to the northern perimeter of the city to track down the villain, Oshii lets loose with his favored cinematic technique: the pensive, elegiac moment, stretched to near-absurd extremes. For once, CGI is used to artistic effect instead of the usual cheap spectacle–vast swarms of seagulls spin across a pageant of decaying future architecture, an inexplicable street parade of puppet-gods erupts during a snow flurry, a brass clockwork fantasy tower houses a mechanical man hiding inside nested virtual worlds. This is a big-screen experience that no DVD could ever do justice.

Innocence is a challenging film, heavy with concepts as well as mood. Oshii has raised the bar again for what an animated film can communicate, and the results are stunning.