The relationship between America and the Marshall Islands began during World War II when the United States liberated the island from the Japanese. In 1947, the connection was formalized as the United Nations “gave” the Marshall Islands to America to be held in a protective trusteeship. Half-Life begins with some optimistic old images of the singing-and-dancing native islanders welcoming their new “protectors,” the United States military.

According to the protective trusteeship agreement, the United States was responsible for providing for the health and well-being of the Marshall Islanders. As Half-Life points out, however, the United States provided anything but, almost immediately bombarding the islands with powerful nuclear weapons in the interest of science. Archival films show the islanders complying fully with American wishes, dutifully evacuating the Islands every time a bomb is detonated near their South Seas home.

When the H-bomb–estimated to be 500 times more powerful than previous nuclear weapons–was dropped in 1954, however, the islanders were neither warned nor evacuated. It is this action that brings up Half-Life's most disturbing question: Did the U.S. government knowingly use the Marshall Islanders as unwitting guinea pigs to study the long-term effects of radiation? The most compelling evidence comes from military weathermen who were stationed on the islands at the time of the H-bomb test. These men were also exposed to the effects of the radiation, and know all too well how convenient the isolated population of islanders were to testing the effects of nuclear fallout. One of these ex-military men introduces himself by showing off the contents of his wallet, including NRA and Moral Majority membership cards. He's a dyed-in-the-wool all-American, ultraconservative patriot, but even he has serious questions for his government.

Interviews with the surviving Marshallese, are counter-pointed with propagandistic old films shot by the Atomic Energy Commission. One film shows several of the young Marshallese men being taken to Washington D.C. during the '50s. They are described as “happy, amiable savages.” Though one has to wonder exactly who the savages are when modern-day Marshall Islanders show off photo albums documenting the early funerals of all those young men.

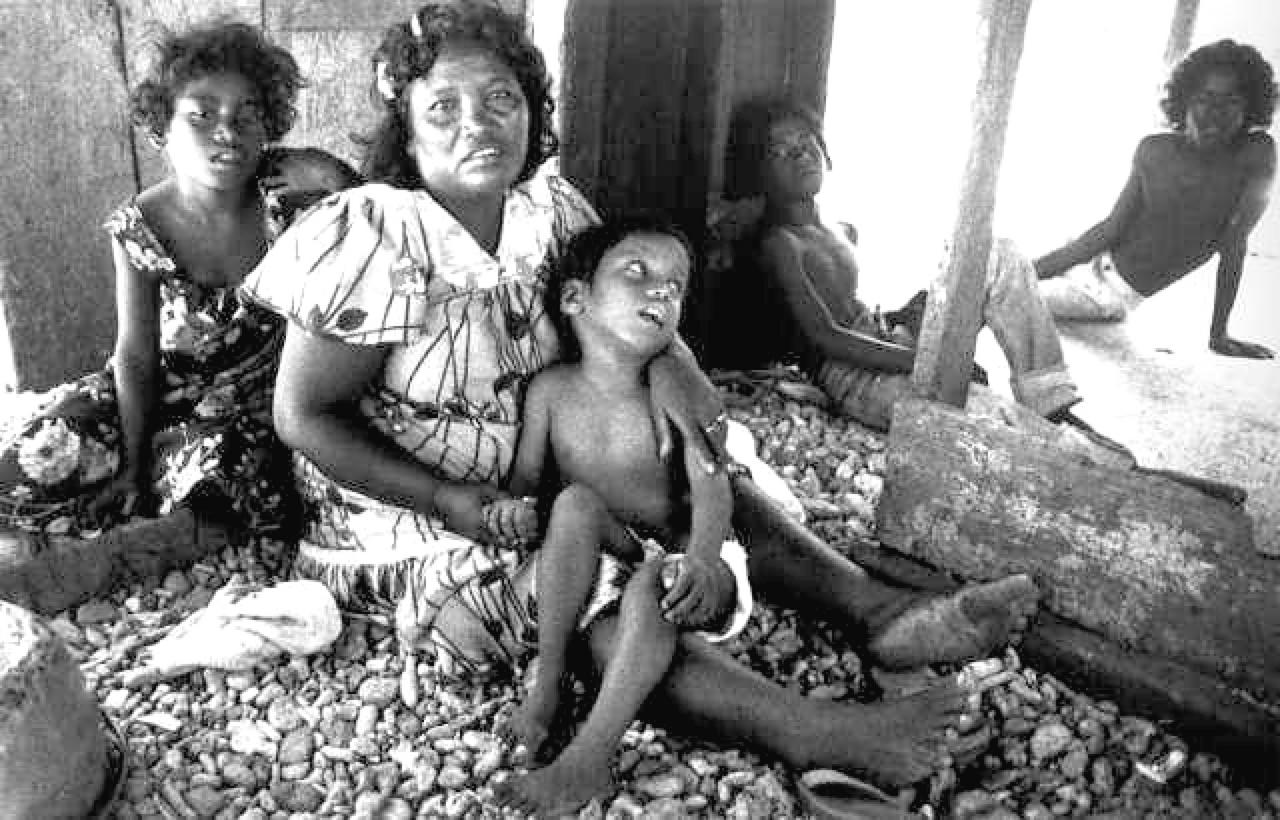

That the Marshall Islanders suffered (and continue to suffer) from an alarmingly high rate of cancer and birth defects in the wake of all those nuclear tests is hardly surprising. Given that hindsight is 20/20, we can even cut some slack to military officials for not fully grasping the deadly effects of nuclear weapons back in the '50s. The scariest part of Half-Life, however, is the United States' earnest, ongoing attempts to abandon the Marshall Islands. Current footage (from the '80s, anyway) shows lawyers attempting to state the case for the Marshall Islanders in front of Congress. Everyone acts very concerned. Then big daddy Ronald Reagan comes out and declares that the Marshall Islands are “all grown up” and don't need the protective trusteeship of the United States any more. The Marshallese are left to their own devices, their contaminated lands and their ongoing diseases. … Nobody said it was a parable with a happy ending.

O'Rourke's film sounds overwhelmingly depressing. But, somehow, the director keeps things from descending into total bleakness. The clever use of archival footage gives the film a blackly comic sense of irony. The islanders, abused as they have been, are a hearty, admirable lot. And O'Rourke's lovely cinematography gives us a perfect “Shangri-La” sense of this disappearing tropical paradise. The Cold War may be over, but Half-Life proves that its effects will never fully die off.