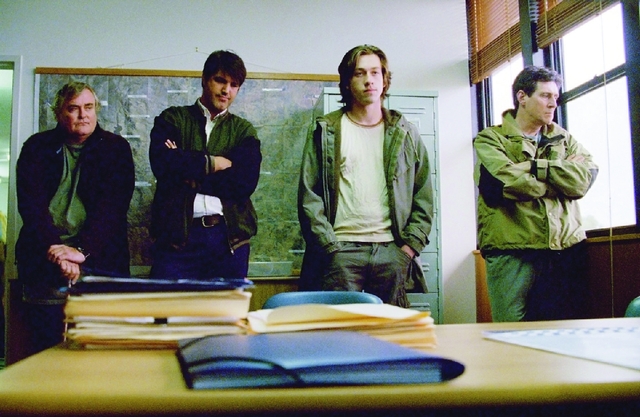

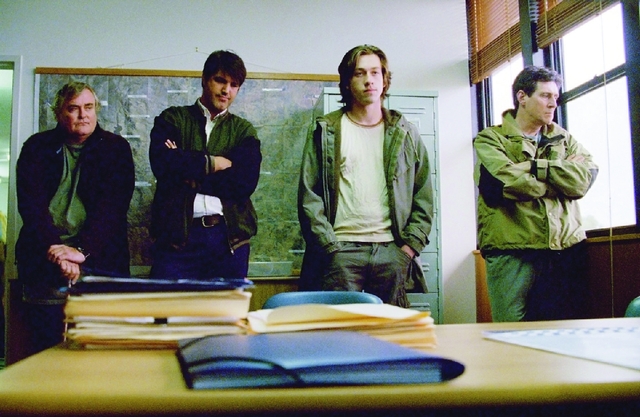

Jindabyne

Aussie Drama Contemplates Topics Of Love And Death (Mostly Death)

“That better not be the Jaws music I hear.”

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992

“That better not be the Jaws music I hear.”