Of all the documentaries to be released this year, Lost Boys pulls the least punches and does its best to refrain from condescension. As a result, it ascends beyond its own purpose (that of political protest) without really performing it, emerging as an affective but tame meditation on cultural disillusionment.

After being rescued from a devastating civil war in which two million Sudanese were slaughtered, 4,000 young boys, orphaned by the calamitous war, were stationed at a UN camp in Kenya (where they remained for nine years). These young survivors then relocated to new homes around the United States. Contrary to what they were told about America, the “lost boys” are introduced to a world of cynicism, suspicion and distrust. After facing such astonishing plights in Africa, their hopeless, unceasing faith in America portends incremental heartbreak.

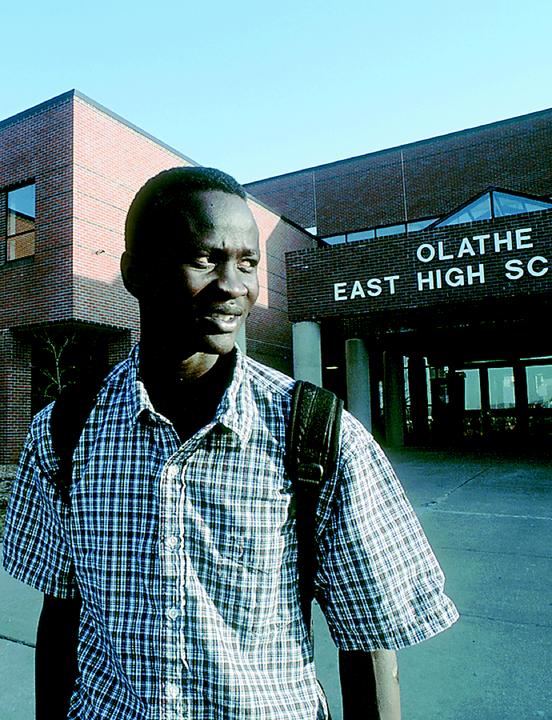

Filmmakers Megan Mylan and Jon Shenk follow two of the lost boys, Peter and Santino, from the mud huts of their Kenyan village through the first year of their life in “a land called Hawston” (Houston). It isn't long before Peter and Santino learn about social caste systems, deodorant, electric stoves and other colorless Western banalities, only to later concede “there is no heaven on Earth.”

The lost boys are approached and befriended by their Christian sponsors, each of whom seems to play the role of missionary while attempting, often in vain, to ignore the cultural differences that separate the Sudanese from their western counterparts. One cannot help but balk (as intended) at the film's most woeful scene in which a group of teenaged Christian “faithfuls” sings and chants in perfect, menacing unison, tears of appalling sincerity streaming from their eyes and pizzas dangling from their lips. These kids are still in high school, afflicted with acne and youthful disenchantment, yet they have already pledged their undying allegiance to the largest cult on Earth. When the camera arrives on Peter, sitting in the back of the room, staring forward as thoughts of loneliness and isolation invade his mind, the audience (despite whatever spiritual attitudes it may bear) is challenged to face the darker, more exploitative aspects of organized religion.

When searching for terms with which to describe the film, words of such morbid magnitude as “poignant,” “moving” and “touching” flashed through my mind. The effect of the film, however, is quite upsetting, although not entirely enlightening. This is not a criticism; rather, it is to the film's credit that the directors never stoop so low as to urge the audience into “helping these poor souls.” With Lost Boys of Sudan, we are given a genial, inoffensive, quite digestible piece of work, one that lingers in the memory but does not have the power to scathe; this is a criticism.

Too short by half (90 minutes), the film is so amiable and inconclusive that one might find oneself split between feelings of endearment (toward the boys) and a strange lethargy. These boys may be struggling in the U.S., but, had the directors equipped us with the information needed to truly understand the dire situation in Sudan, the conditions in America might not seem so lamentable.

As pure human drama, though, the film has empathy to spare. This, in the end, is what saves the picture from falling victim to its own ambiguity. It is a testament to the directors' fine sense of storytelling, and compassion that the film attains such a remarkable intimacy. To say that Lost Boys is about the delicate relations between longing and belonging suggests an unabashedly precious approach to a subject that is already flooded with good, if grandiose, intentions; Shenka and Mylan take another route, employing a technique as crisp and efficient as its running time would suggest, and the film's simplicity only adds to its cumulative effect.

Even if Lost Boys' melancholic tone is appeased by one of aching respect and sensitivity, it's also potent, bittersweet and hopelessly wistful. In this case, that is a good thing.