Now, Brits Gaiman and McKean have collaborated again. Gaiman once more takes pen and paper in hand to script a fairy tale for adults. McKean, however, trades his inks and paints for a movie camera. As the opening credits inform us, Mirrormask is “designed and directed by Dave McKean.” That is a highly apt description, as Mirrormask is as much an art project as it is a narrative film.

The film follows in the grand tradition of Alice in Wonderland, The Wizard of Oz and Labyrinth. (No small wonder on that last one, as much of the creature fabrication here has fallen to the Jim Henson Workshop.) The twist this time around is a subtle, but important one. Our heroine Helena (Stephanie Leonidas) isn't trying to escape her humdrum existence. In fact, her parents own and operate an avant-garde Cirque du Soleil-style circus. Surrounded by jugglers, contortionists and (heaven help the girl) mimes, 15-year-old Helena dreams of running away and joining “real life.”

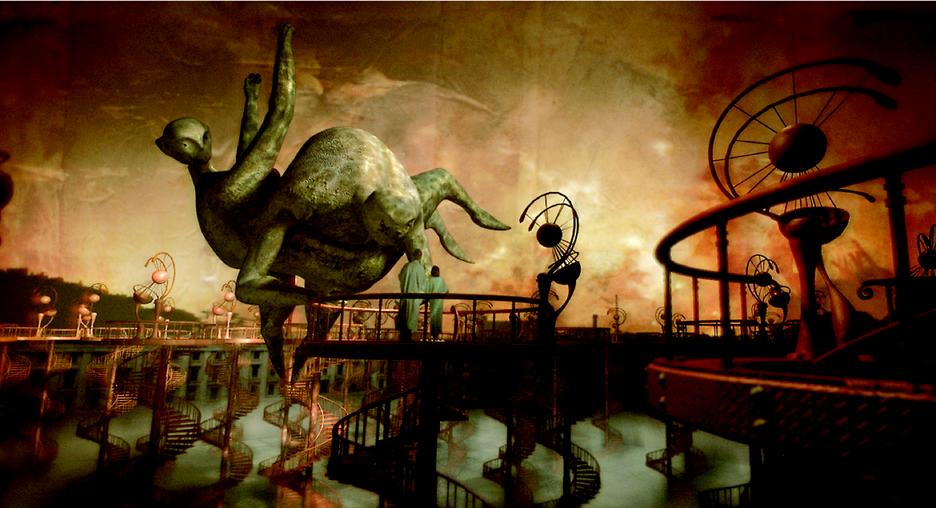

One day, following a nasty argument, Helena's mother (Gina McKee from Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants and Notting Hill) falls ill. Helena hides her fear and guilt by losing herself in art. It seems the teen is a prodigious doodler, covering the walls of her bedroom in fantastic sketches (provided, of course, by director Dave McKean). On the night of her mother's critical operation, Helena falls asleep and wakes up in a bizarre alternate world that seems to be inspired by her drawings. Creepy towers stretch into a sepia-toned sky. Books are alive. Inky fish swim through the sky. Riddle-hungry sphinxes prowl the smudgy alleyways. And everyone wears a mask. Except Helena, of course, who sticks out like a sore thumb.

This unnamed world, it would appear, is split between the City of Light and the City of Shadows. The City of Light is being overrun by darkness because the young Princess of Shadows has run away from home. She was sheltered, briefly, by the Queen of Light (also Gina McKee), who now lies in a deathless sleep. Most of the creatures Helena runs into seem to think she is the runaway princess–including the menacing Queen of Shadows (McKee yet again).

Able to view her own bedroom through the windows in her drawings, Helena soon determines that the Princess–who looks just like her–has traded places with her and is now living her life back in the “real world.” Helena, with the help of a masked juggler named Valentine (Jason Barry), searches for the titular magical talisman which will help get her home.

The world created in Mirrormask is an amazing one. On purely visual terms, Mirrormask is one of the most original films you are likely to see this or any other year. McKean's artwork has always been a sort of multimedia, multilayer collage. In Mirrormask, it's hard to differentiate between real people, masked performers, puppets and computer animation. Despite a contribution from Jim Henson's company, Mirrormask looks nothing like Labyrinth. It looks, quite expectedly, like a living, breathing Dave McKean painting. Some might find his style a bit too sketchy, a tad too murky–like Ralph Steadman on … well, Ralph probably did every drug in creation. Whatever: It's weird. Art is a matter of taste and, personally speaking, I dig McKean's work.

There are those, of course, who will dismiss Mirrormask as nothing more than a flight of visual fancy. I would, however, disagree with that assessment. Gaiman's script is subtle, but features an interesting storyline that goes beyond the typical fantasy quest. The film does require viewers to accept a sort of “dream logic,” but the film's plot holds together quite solidly.

Most stories of this type exist on both physical and metaphysical planes. Like Dorothy's trip to Oz, this entire tale could be chalked up as simply a paranoid nightmare on the part of a troubled kid. Or it could be viewed in purely fairy tale terms. Perhaps Helena has inadvertently traded places with an extradimensional princess. The film works best, however, when you start to key into Gaiman's subtext. Like Alice in Wonderland, Mirrormask is a nonsense-soaked parable about puberty. Helena's “dark princess” is little more than her own fear of growing up, of being a girl who dresses differently, argues with her father, smokes cigarettes and kisses boys.

The bottom line is, if you don't like McKean's style, you won't like this film. Despite the script assist from Gaiman, it is McKean's film through and through. For some, this dark, original, visually arresting fantasy will become a cult favorite. For others, it will simply rest a few confusing notches below the classics.