Sean Penn's new acting tour de force, The Assassination of Richard Nixon, is a '70s-style movie in every sense of the term. It's not merely that the film is set in a gritty-enough recreation of post-Vietnam-era America. It's also that the film has the same slow, dark vibe as many of the above-mentioned films.

Penn (whose career seems composed entirely of highlights at this point) is at his best playing Samuel Bicke, a real-life furniture salesman who, in 1974, took it upon himself to assassinate President Richard Nixon. Sam Bicke was to salesmen what Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver was to hacks–a misfit loser who ended up seeking redemption through violence. As history bears out, however, Bicke was markedly less successful in his use of violence.

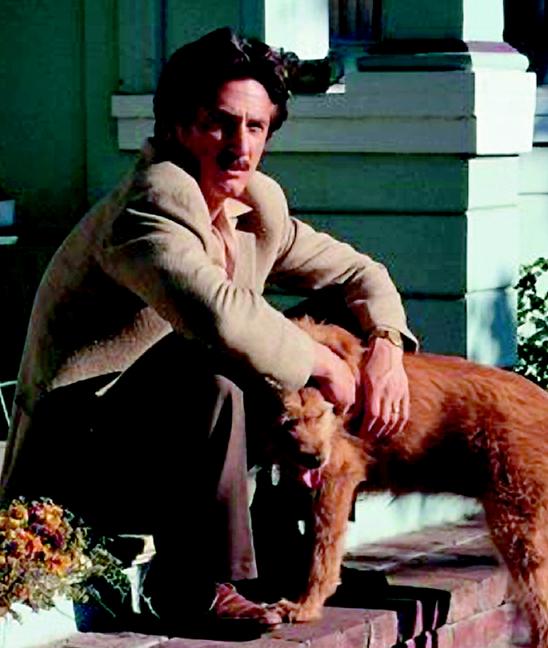

Penn simply melts into the cheap suit and mealy mustache of Bicke, a total schlub who was separated from his wife (a glammed-down Naomi Watts), saddled with a go-nowhere career and buried under a mountain of self-doubt. The film is in no hurry to lay out its narrative. Like most of its '70s predecessors, this is a drama entirely driven by character.

As we meet him, Bicke has a death-grip on his own fading shreds of the American Dream. He believes that a mobile tire-changing service (with patiently supportive pal Don Cheadle) is his key to financial success and a reunion with his estranged wife. The scenes between Watts and Penn are among the most painful in the film. We know from her first guarded appearance that she no longer wants anything to do with this man, but our boy is too deluded to pick up on her all-but-unsubtle body language. Unable to get any attention from wife or children, he simply takes solace in the fact that the family dog is glad to see him.

As he hounds the Small Business Administration for a loan, withers under the thumb of his demanding type-A boss and continues to shadow his “sorry but I've moved on” wife, Bicke's anger slowly festers. Sitting in his crappy rented apartment watching television, Bicke starts to see newly re-elected President Richard Nixon as his ultimate enemy. Nixon, after all, doesn't have anything that Bicke doesn't. Bicke's white, middle-class, educated. Why can't he catch a break? When a colleague describes Nixon as “the ultimate salesman”–a guy who promised he'd get America out of the war, didn't and was then re-elected on the same failed promise (sound familiar, anyone?)–Bicke makes up his mind.

The film–the first to be directed by Tadpole scripter Niels Mueller–carefully chronicles Bicke's daily miseries and his slow slide into mad, misplaced anger. When he embarks on his final attempt at blood-soaked redemption, viewers are apt to find themselves reminded, once again, of Taxi Driver. Slowly paced and never quite revelatory, Assassination comes out worse for wear in that particular comparison. Still, it's got it own strengths. It digs a bit deeper into the vast social and political schism that divided America in the mid-'70s and, for that reason alone, feels eerily timely.

The film is, to put it succinctly, a downer. But that shouldn't frighten away viewers. There are moments of rich humanity throughout, all of it rooted by Penn's sadly sympathetic portrayal. The film even flirts with some of the sneaky, sad humor Mueller displayed in Tadpole, as when our poor, oppressed protagonist attempts to join the Black Panther Party.

With a bad economy, outrageous gas prices and an overseas war that seems increasingly like a quagmire, maybe we're not so far removed from the '70s. Perhaps there are lessons to be learned from this uncomfortably real examination of frission-filled America and the cruel detritus of broken promises and failed dreams.