The film came to life thanks to actress Neve Campbell (Scream, “Party of Five”), who was classically trained as a ballet dancer before embarking on her career as a Hollywood actress. Campbell has always wanted to find an outlet for her dancing skills and partnered with screenwriter Barbara Turner (Pollock, Georgia) to write, produce and star in what eventually became The Company.

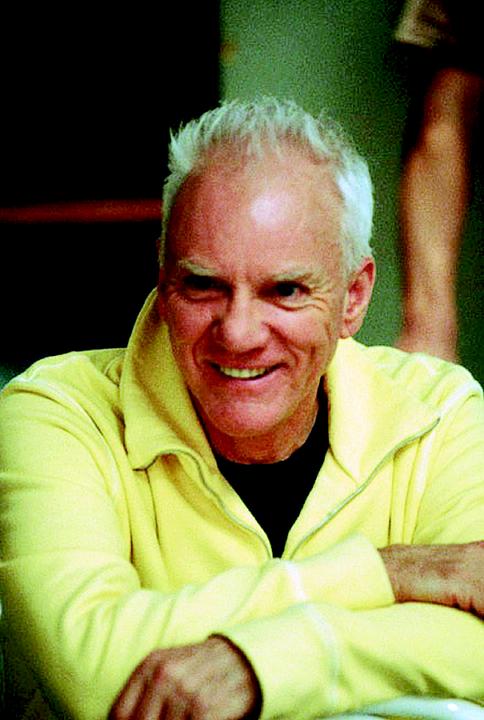

Though Altman came into the project quite late (apparently after a great deal of arm-twisting), the end product looks and feels quite a bit like a classic Altman effort. Set behind the scenes of Chicago's real-life Joffrey Ballet, the film is a loose, largely improvised exercise in time and place—though not, it must be stated, in character and story. There is precious little in the way of script here. We eventually come to realize that the ballet company in question has a young ingénue named Ry (Campbell, of course) who gets a shot at a feature role thanks to that age-old show biz cliché, the suddenly injured lead performer. We also learn that the company is run by a sweet and sour autocrat (the oddly cast Malcolm McDowell). We know that … um, a lot of the dancers sleep with each other. But that's pretty much it for the plot details.

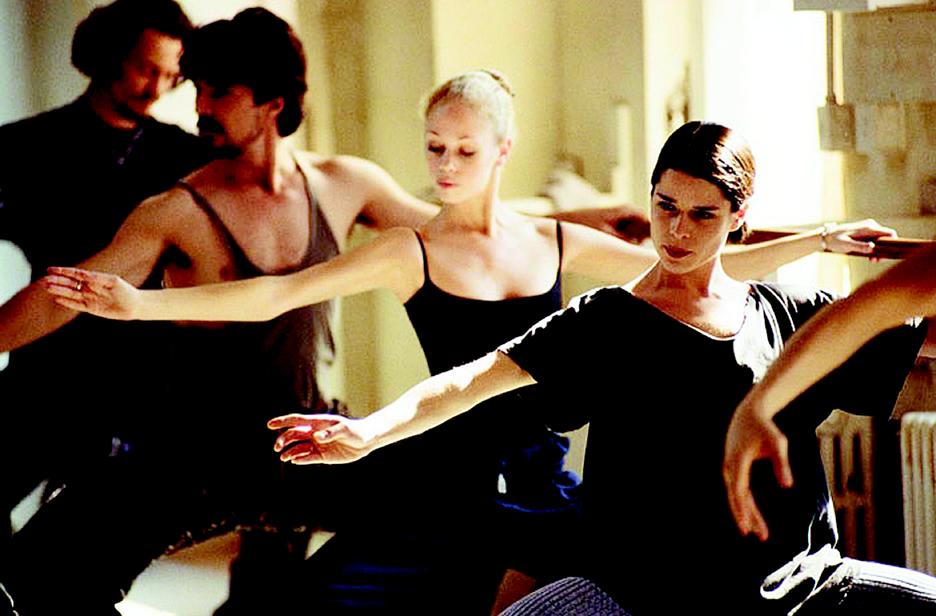

The film takes place over the course of a year in which the dancers work crappy jobs to make ends meet, practice, injure themselves, get fired, party, get married and put a lot of tape on their feet. At least 60 percent of the film consists of Joffrey Ballet performances. If you are a fan of classical/modern dance, then you'll certainly be getting your money's worth here. The performances are beautiful and innovative, utilizing members of the real Joffrey Ballet company. Of course, this limits Altman's ability to create an in-depth drama. Finding real actors who can actually perform classical ballet rules out most of Hollywood. (Bruce Willis, for example, is right out.) Aside from James Franco (Spider-Man) in the minor role of Ry's chef boyfriend, there are basically no other recognizable actors. That means most all the roles in The Company are taken up by non-actors. Few of them are asked to recite more than a single line.

The few moments of character drama that do exist are pushed quietly to the background. (Don't look for any kind of character arc, dramatic build-up or narrative wrap-up.) In time (the film is a long, slow 112 minutes), we start to realize that The Company is more about process than people. Midway through, an artsy French director shows up to pitch his new project, a rather preposterous modern ballet involving blue snakes, dancing zebras and hungry giants. Initially, this seems like it's going to be a target of satire for Altman (who's never been above biting the hand that feeds him). In the end, though, we see large chunks of this avant-garde production and realize that—following all the pain and practice—things have come together quite spectacularly. Dance, like film, is all about the end result. We get you, Robert.

The Company is, quite honestly, a strange production. It gives audiences little of what they could reasonably expect to see walking into the theater. It's more of a documentary than a drama, but doesn't show off anything we didn't already know. The “fly on the wall” narrative tells us less about the business of show business than the average episode of “American Idol” would. The script doesn't bother to create any compelling characters or give them anything dramatic to do besides dance. … And yet, there is something lyrically compelling about the film. The Company, like director Robert Altman's career, is an unpredictable, elegant mess. Those attracted to the world of dance will probably revel in the film's microscopic moments of artistic discovery.