Taken For A Ride

Residents Battle Bmx And The City

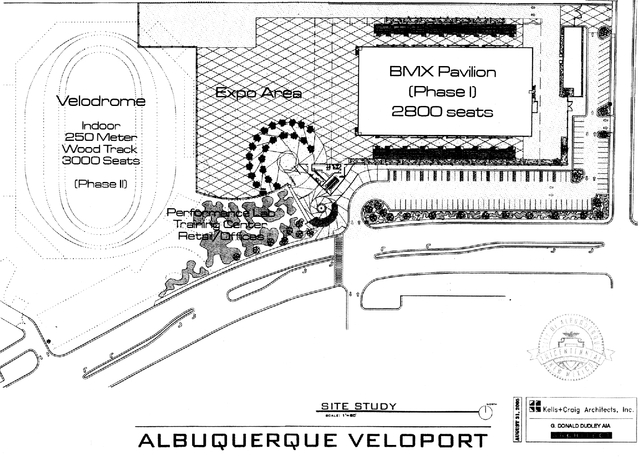

The actual layout of the BMX track, not approved by residents, where the track replaced the tennis courts, directly abutting the neighborhood

All that separates Mary and Felix Trujillo’s house from the BMX track is a narrow street.

Xavier Mascareñas