A Man Called Destruction, published on March 24, presents the reader with an unflinching portrait of the artist as a wrestler-with-demons working toward redemption. Chilton is best remembered as a gifted creator who fought to recover from the trauma of young fame by navigating a stormy sea.In this account by biographer Holly George-Warren, Chilton drifted, plumbed dark depths and eventually arose to a surface permeated with adulation for his work and influence. His sudden death in 2010 transformed him into the stuff of legend.George-Warren’s book isn’t so much rocanrol hagiography as it is cultural biography, as its author views her subject as quintessentially American. A fair amount of pages in this narrative are devoted to establishing a baseline, including numerous anecdotes about formative childhood and adolescent experiences, the ascendant quality of post-war life for white American veterans and their progeny and the profound effect such stuff had on Chilton’s musical trajectory.Of course, none of those cultural accoutrements can be invoked without ironically suggesting them—as the text does—as reasons for Chilton’s disdain of fame and fortune; his ultimate rejection of accomplishment can be seen as a result of dissatisfaction with the ease of bourgeois life. The son of creative and accomplished parents, Chilton spent a good portion of his life retreating from the bright lights and sharp shadows generated by both his predecessors and himself.By the time Chilton recorded “The Letter” in 1967, he was already a veteran of the Memphis rock and roll scene. Having played in one of the area’s most popular garage bands, The Devilles, the 16-year-old rocker moved up the ladder with his gritty voice and an instrumental style that years later caused Tom Waits to reference Chilton as the “Thelonious Monk of rhythm guitar.” Despite raves from folks like Lester Bangs and a growing fan base, Chilton decided to leave The Box Tops in 1970. After some tentative work done in New York City, he eventually returned to Memphis where he began working with Chris Bell. The result was Big Star.The story of Big Star is a tale of definition. As Bell and Chilton worked together, they fashioned an intricate object called power-pop. The kids went wild, but innovation didn’t equal commercial success. George-Warren reports the reaction to Big Star’s third record was less than stellar; A&R icon Jerry Wexler reportedly told a band member, “Baby, listening to this record made me very uncomfortable.”Chilton despaired over this, and he began to see his work with Big Star as a failure. Always a partier, the musician embraced a serious drug and alcohol problem as a result of his perfectionist nature. Chilton’s love-hate relationship with fame and the ongoing high expectations and critiques of his music continued to take their toll post-Big Star.Bell’s untimely death in 1978 served as an opportunity for Chilton to take stock; he began work on reinventing himself as a musician whose legacy would be defined by an unwillingness to compromise, a tendency toward heartfelt expression, the ability to nail wondrous hooks and killer chops.While he spent some of that time in self-exile—often working menial jobs and living in obscurity—Chilton’s music is now seen as a central and guiding voice in the history of American rock and roll, an accomplishment George-Warren’s biography makes almost as clear as listening to Chilton play and sing does.

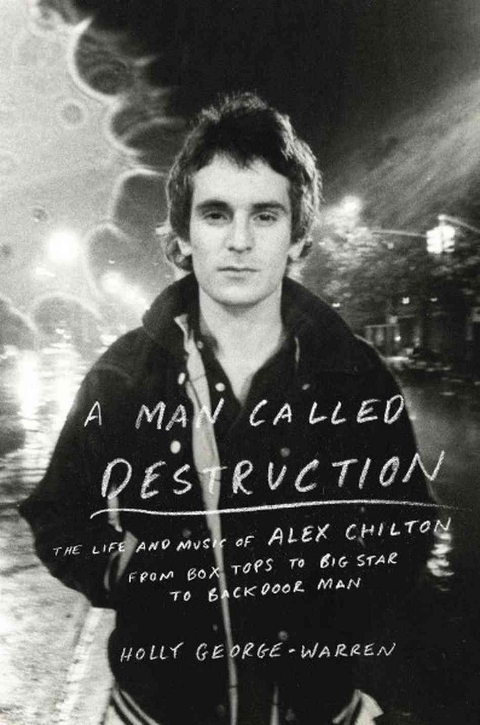

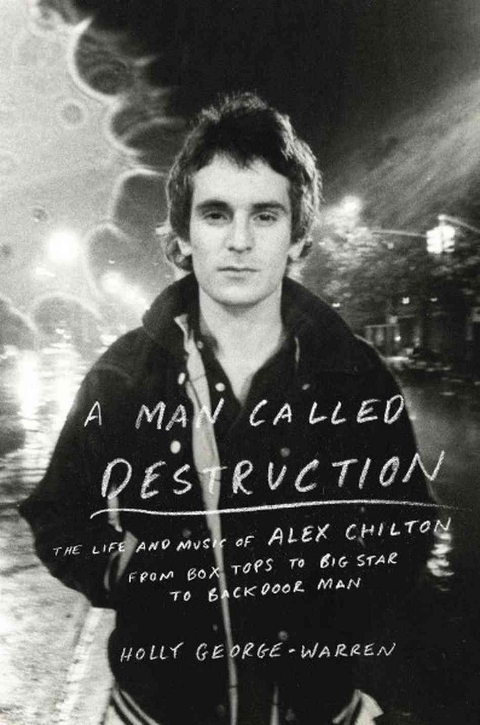

A Man Called Destruction: The Life and Music of Alex Chilton, From Box Tops to Big Star to Backdoor Man

Holly George-WarrenViking Adulthardcoverbiography$27.95