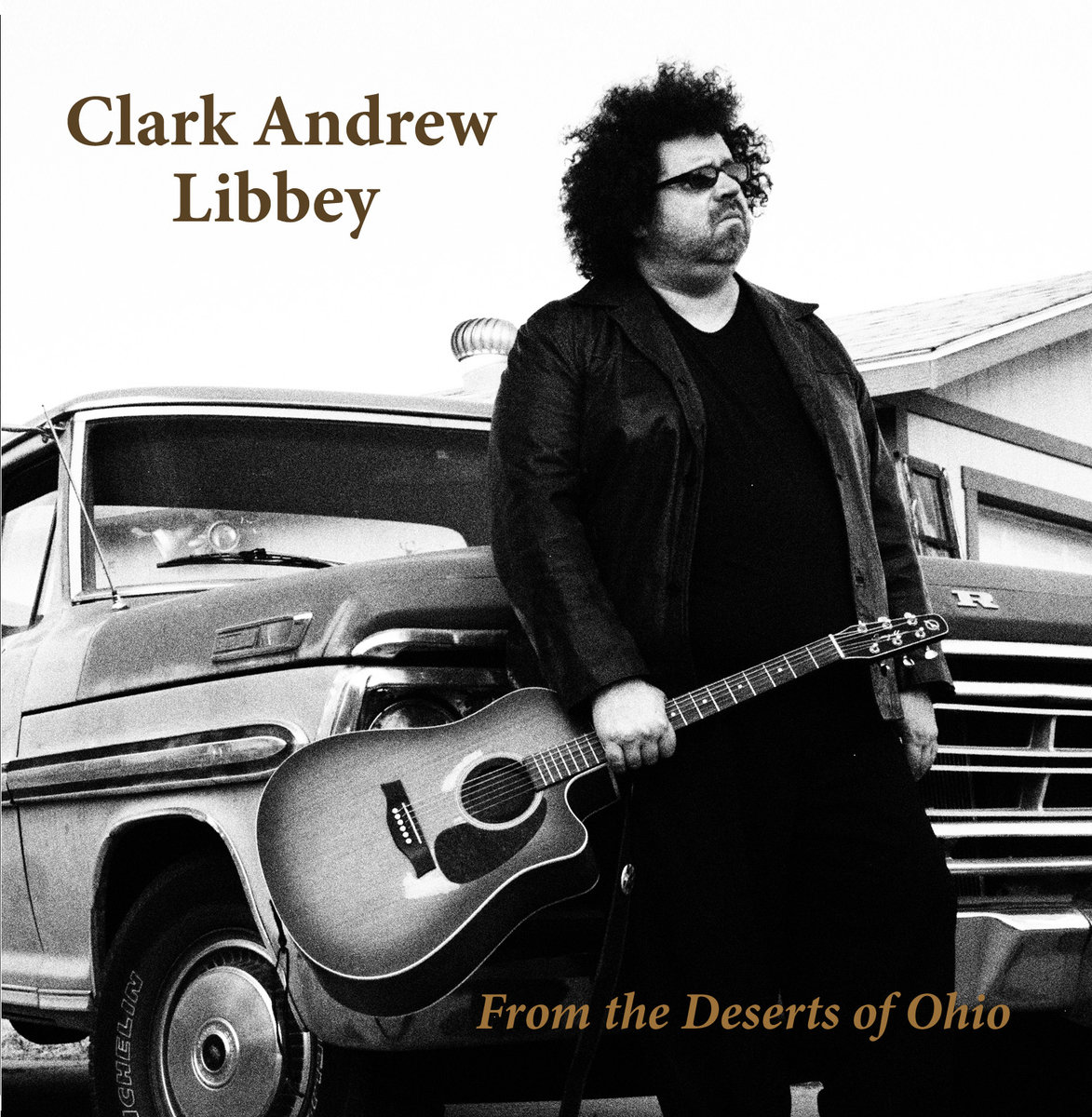

Early on into the second track of his latest recording, alt. Americana crooner Clark Andrew Libbey offers insight into what he really sounds like, singing resonantly but somehow still mournfully, “Like a hillbilly time machine, like a backwards country song,” setting up a deeply felt conceit that the musician explores in depth—with music and words—throughout the recording. In the world depicted in “Rooftops,” no one is really listening to the sadness the singer documents, but his duty to art and life require that a song built on tradition and executed with plaintive beauty be presented as evidence of the journey. These songs of innocence and experience fill the wide and dusty expanses of From the Deserts of Ohio, offering color and commentary on a heartbreakingly honest place that Libbey wishes angels would take him from. As usual Libbey’s singular vocalizations add to this sprawling selection of acoustic sentiments.

Wake Self Malala (Self Released)

Wake Self uses hip-hop to develop the social and cultural conscience of his community in Burque. While on the surface, that may seem to be a pedantic or revelatory statement, it’s really just a reflection of the dude’s music and words. At their roots, the rap works of Self display a plangent poeticism that rises from his concerns for the other. In combination with samples of melody taken from unlikely, obscure and thus totally awesome sources, a glitchy, syncopated sense of rhythm that jitters as much as it flows over complex sentences—and blank verse that buoys the struggle for life without romanticizing or idealizing material outcomes—Malala succeeds where other local rap projects fail. Wake Self is on a spiritual journey and this album reflects that. More importantly it seeks to forcefully deconstruct the misogynist myth of hip-hop many of today’s youth still find alluring. With Malala, Wake Self just wants those kids to wake up.

Sorry Guero DonÕt Call Us, WeÕll Find You (Self Released)

This is rough, hard-edged, man music about a world in decay. It’s about how a slapped out bass line can intertwine with a deadly and crunchy guitar sound to make a vocalist become darkly guttural and animal-like in expression. The drums beat out a murderous agenda. And by the way all of that is relentless, drawing listeners in with tracks like “The Worst is Yet to Come,” and proceeding through the miasma of tuneage like “Run From the Swine,” a killer composition that’s ostensibly about the death of James Boyd and provides the most coherent musical vision of the album’s 11 intense tracks. There’s only one reprieve; the band’s primitive yet plaintive take on a Van Halen classic at the end of Don’t Call Us is both disturbing and damned amusing.