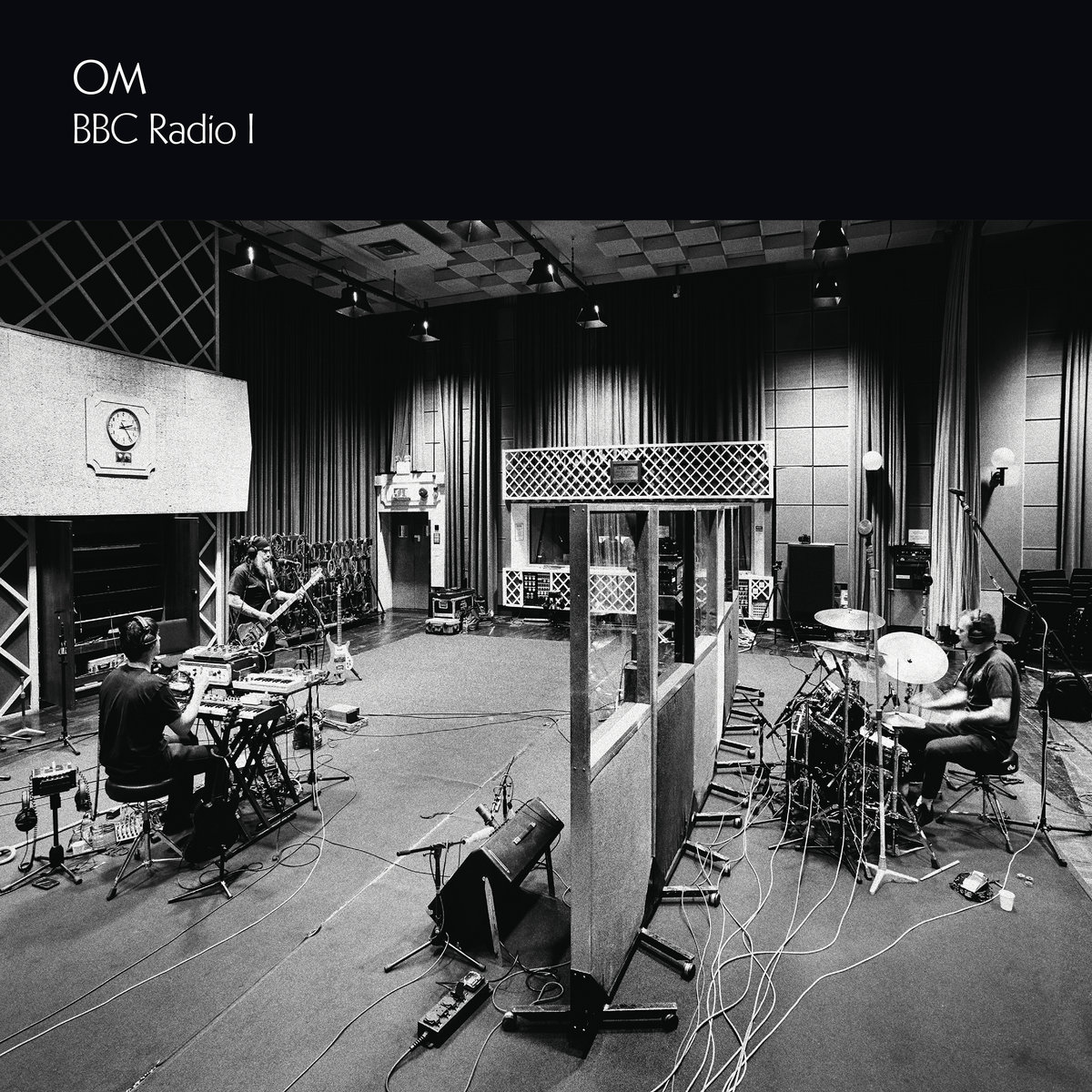

Music Interview: A Sacred Syllable At The Beeb

Om Releases Historic Bbc Sessions

OM

courtesy of the artist

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992

OM

courtesy of the artist