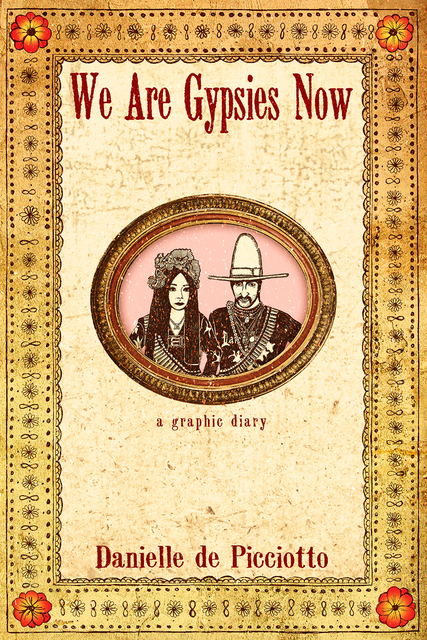

Rock Reads: We Are Gypsies Now

Picciotto Book Explores Boundless Experience

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992