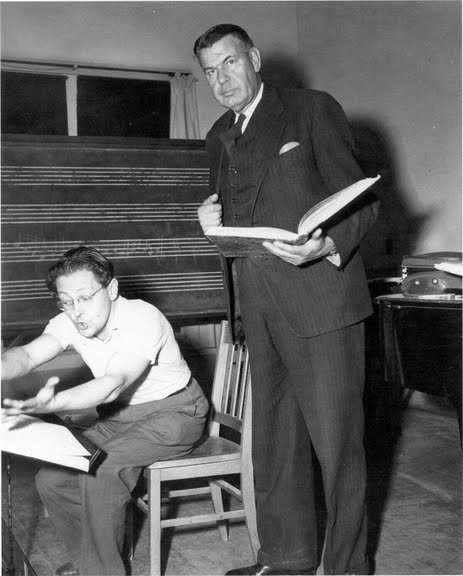

This month marks the 30th anniversary of the Robb Trust, a New Mexico academic institution that manages the legacy of one John Donald Robb. Robb was the dean of the College of Fine Arts at UNM for many years, leaving this West for the southern realms at the tender age of 96 years old. More importantly though, Dean Robb’s work as a composer and ethnomusicologist continues to provide both a template and a mythos for the past path and future trajectory of folk music in New Mexico.Robb spent hundreds of hours making field recordings of every local event he could travel to in this vicinity, from local hoe-downs in Pie Town to ritual dances and drumming sessions at Pueblo sites. He also wrote art music—operas, cantatas and chamber music—that was as informed by his study of Modernism as it was by his exposure to New Mexican music. In his later years, he became a musical experimenter and proponent of electronic music.In many ways John Donald Robb represents the essence of what New Mexico was to become in the latter half of the 20th century—informed by a multitude of cultures, capable of absorbing the new as readily as hewing to tradition and always revisioning oneself with an eye toward the future.Robb was a Minnesotan who attended Yale about 100 years ago. He also studied with famous musical Modernists like Darius Milhaud and Nadia Boulanger. Robb went to practice law in New York City as a young man, before the magic and music of the West drew him away from Atlantic shores and to the banks of the Rio Grande.Ahead of the concerts and films celebrating the life and work of this important Burqueño—happening this week at the National Hispanic Cultural Center—Weekly Alibi chatted with UNM Distinguished Professor Emeritus Enrique Lamadrid—himself a musicologist and researcher of Robb’s life and work—to find out more about Dean John Donald Robb.We talked about music and culture and the people at the center and on the edge of Robb’s creative life. Here is a vivid snapshot of that dialogue.Weekly Alibi: Dean Robb’s legacy is huge, especially with regard to the documentation and preservation of New Mexico folk music. Could you tell our readers a little bit about that?Enrique Lamadrid: It’s a sizeable archive. He took on the task—from when he first came here—he was tasked with keeping track of the music, all of the music that’s out there. There are many, many layers of musical culture in New Mexico, dating back as far as as you want to take it. Before the arrival of the Spanish and after the return of the Spanish-Mexicans—after that first very difficult century that they were here—there were different kinds of music. All kinds of music can be found in the Robb Archives. There is Native American music from New Mexico and from the Sierras in Mexico, from the Tarahumara, and further south into Oaxaca. He also recorded a lot of Nuevo Mexicano and Tejano music and, then, a bunch of cowboy music, too.And these were field recordings that Robb made to research music in New Mexico?He sure did make recordings. He was always using the cutting-edge technology of the time for these field recordings. He went through all forms, but I’m not sure if he made wax recordings. Everything in the archive has been digitized, you can’t always tell what the recording source is. But I know for a fact that he used [magnetic] wire recorders, the kind that came out right around World War II, in the 1940s. They looked like reel-to-reel recorders but it was reel-to-reel-wire. Robb made sure he always had the best possible recording equipment.What is the status of Robb’s musical artifacts?They’ve migrated to different media, they’ve been digitized. For a while the archive was on these big pancake-sized magnetic tapes, I mean big ones, 14-inch discs. They used to call them pancakes. But with that sort of recording, the medium itself can deteriorate and recordings might be lost.Was there an overarching vision or agenda to Robb’s recording activities?He didn’t always understand exactly what he was recording, but he did a huge service to all these cultural communities in New Mexico, using the best technology he possibly could. Of course, we still study these recordings today. A lot of the archive is online. And the archive grows; I contribute to it, there are other collections within the archive that are still growing. As time goes by, those recordings become more and more precious. That’s the Robb legacy.Which recordings stand out?They’re all fascinating, but people can hear what was going on in New Mexico village fiestas in the 1950s, the kind of ballads and dance music that was being performed. You can hear that stuff.Robb also studied with modern masters, composed art music and experimented with electronica but seemed to have an overriding interest in the West, in New Mexican culture. Discuss.He was a very successful lawyer who had a passion for music. He had a great musical education.Yeah, he studied with Milhaud and Boulanger, which is pretty impressive.I think that helped get him into UNM. He didn’t have a conventional degree in music, but he had all of this on-the-ground knowledge of the musical world, he played different instruments. He was very adventurous, one of the first to work with Moog synthesizers.Yeah, I remember one of the first electronic music labs at UNM, run by Darrell Randall and Wes Selby in the mid-1980s, used a lot of Dean Robb’s equipment.Yeah, I arrived at UNM in 1985. And so I met him before, through his family and those first years at UNM, he was still around, on and off campus and at the Fine Arts Library [which was then housed within the main College of Fine Arts Building]. I got to interact with him and he always encouraged my work. A lot of the breakthrough moments for me came just listening to some of his recordings. There’s some very hybrid musical forms out here in New Mexico. What you might call Indo-Hispano music made by enculturated Native communities. But you can hear musical forms that draw from both traditions by listening to the music in the archives.How would you characterize Robb’s involvement in the documentation and preservation of New Mexican music?He was just part of an appreciative audience and he had access to a microphone. There are people trying to say “This is the great patriarch,” they try to romanticize that, try to romanticize him. I don’t think he’d be comfortable with that. He just made the best recordings he could and used the melodies of New Mexican folk music—much like [Béla] Bartok used Balkan folk music—in his compositions. He had a great deal of respect for the musicians and for the traditions he immersed himself in.

Celebrating the 30th Anniversary of

the UNM John Donald Robb Musical Trust

Musica del Corazón: Sin Fronteras withFrank McCulloch • Cipriano Vigil • Lone PiñonWednesday, Nov. 13 • 7:30pm • NHCC Journal TheatreThe Musical Adventures of John Donald RobbFeaturing Selections from Joy Comes to DeadhorseThursday, Nov. 14 • 7pm • NHCC Bank of America TheatreNational Hispanic Cultural Center • 1701 Fourth Street SWThese events are free and open to the public