Aural Fixation: Only In Oaxaca

Alejandra Robles At Teatro Alcalá

Alejandra Robles

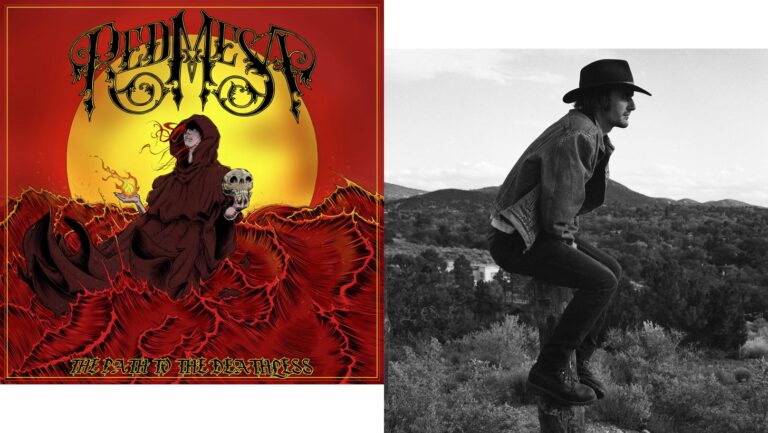

Wings of Freedom!/Wikimedia Commons

Wings of Freedom!