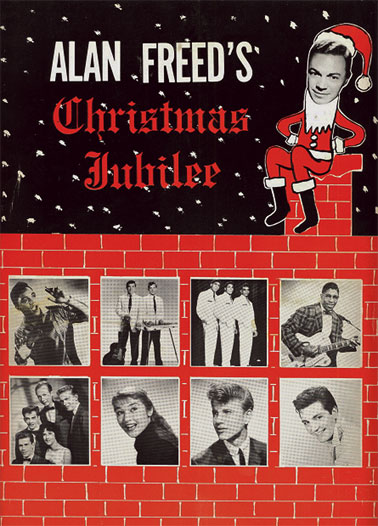

Dick Clark’s April death reminded me of a rock-and-roll Christmas Jubilee concert I saw at the Brooklyn Paramount Theater on Flatbush Avenue during Christmas break 1959.A $2.50 ticket (paid for out of bar mitzvah loot) got me in to see Jackie Wilson, Bobby Rydell, The Detroit Wheels, Bo Diddley, The Isley Brothers, Sam Taylor, Johnny Restivo and half a dozen other acts, plus Hound Dog Man , a full-length feature film starring Philadelphia heartthrob Fabian (Forte) in his first Hollywood production.The rock-and-roll impresario responsible for bringing this all together had been absent during most of the show’s New York run, attending to unavoidable personal business. But on the afternoon I was there, just as the house lights were set to dim for the movie, his familiar, reassuring voice suddenly rose from center stage in a crescendo of brass, twanging electric guitars, and a culminating wave of foot stomping, whistles and applause. I don’t recall the exact words—this was more than 52 years ago—but the essence remains as clear now as when I was a 13-year-old from an upstate New York mill town bouncing in my seat along with 4,000 city kids. We knew something was happening here, and we knew what it was—knew it in our hearts and souls, if not yet our heads.Rock and roll will be vindicated, is what we heard. Square America, go fuck yourself!The personal business that had kept DJ and rock and roll tribune Alan Freed from emceeing the concert was his fight to avoid prosecution for hyping records on air in exchange for under-the-table cash. The practice came to be known as payola, connecting the word “pay” to Victrola, the original brand name for RCA Victor’s record player.Payola ranged from flat-out bribery—a promoter slipping a couple of hundred dollars to a DJ for playing a designated cut in heavy rotation over a specified time period—to more complex and legally nebulous arrangements involving fake songwriting credits, unearned royalty splits, and hidden ownership interests in disc stamping plants, music distribution, publishing, talent management and record labels.By the spring of 1960, Freed and his younger Philadelphia counterpart, Dick Clark, had been called to testify before the U.S. House of Representatives subcommittee on legislative oversight. The appearances went badly for Freed, and much better for Clark. A Career Derailed Freed, the son of a Lithuanian Jewish clothing store clerk and a working-class Welsh-American mother in western Pennsylvania, got his start in 1951 at WJW in Cleveland. In 1954 he moved to New York City radio station WINS, where he popularized rhythm and blues big beat music as a disc jockey via his nightly “Rock and Roll Party” program. He branched out to motion pictures and network television, showcasing artists such as Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Jackie Wilson, Clyde McPhatter and LaVern Baker. By 1958 he was hosting a daily radio program on WABC in New York and a television show on WNEW.Along the way, Freed had accepted gratuities and “consultation fees” from record companies and promoters. He also “shared” songwriting credits and royalties with Chuck Berry for “Maybellene” and The Moonglows for “Sincerely.” When ABC demanded in November 1959 that Freed sign a prepared oath swearing he did not then nor had he ever received payment for promoting musical recordings on the air, Freed refused, asserting in a letter that compliance “would violate my self respect.”He was immediately fired. Five days later, he was subpoenaed to appear before New York District Attorney Frank Hogan, which accounted for why fans didn’t see much of him during the Christmas Jubilee’s Paramount run.Called to testify before the House subcommittee on legislative oversight in April 1960, Freed made for a less-than-sympathetic witness. Although not a Jew according to halachic law (which confers religious identity through matrilineal descent), the Cleveland DJ’s swarthy complexion and prominent nose must have made him seem Jewish enough to the Dixiecrats and Northern Republicans who dominated the proceedings. Freed, after all, had made his reputation introducing “race music” to white kids during his nightly broadcasts. He was known for a steadfast insistence on playing authentic original recordings instead of the more sanitized white covers.In 1957, ABC canceled his weekly television show, “The Big Beat,” because Southern affiliates complained when an African-American guest artist, Frankie Lymon, was seen on a broadcast dancing with a white girl. And Freed was often photographed in the pages of magazines and tabloids wearing bright scarlet tuxedos or outsized window-plaid sport coats punctuated with a wispy silk bow tie favored by African-American or white hillbilly artists. His image as a cultural subversive was cemented at a Boston concert that same year when he allegedly shouted to the crowd, “The police don’t want you to have fun.” It was said to have incited a street riot.Ironically, what ultimately sealed his fate were Freed’s forthright itemized admissions to the committee concerning payments he had accepted from distributors and recording companies as a musical advisor. The fact that ABC had fired him for declining to sign a humiliating all-encompassing oath denying participation in corrupt practices, while not asking the same of the company’s other contract employee, Dick Clark, only deepened committee members’ and the press’ perception of Freed’s corruption. Less than a month after his testimony, the New York City police arrested the disgraced DJ on charges of having pocketed payola amounting to $116,850. American Grandstanding Dick Clark, in contrast, made for a straight arrow and sympathetic witness. The son of a radio professional and solidly middle-class family, he had been brought up in Mount Vernon, N.Y., and earned a business degree at Syracuse University’s Whitman School of Management. His physical appearance before the committee was indistinguishable from the image television viewers saw every weekday between 4 and 5:30 p.m.—an affable, well-mannered junior executive in a white shirt, unobtrusive tie, well-tailored gray business suit, engaging smile and straight neutral hair set perfectly with glistening tonic.Clark became host of the Philadelphia rock-and-roll TV dance show “American Bandstand” in 1956, and took it national on ABC the following year. He was instrumental in launching the careers of local ethnic working-class performers Frankie Avalon, Fabian Forte, Bobby Rydell and Connie Francis. With an eye for anticipating teenage trends and a talent for creating them, he eased the crossover of African-American artists by presenting them to the mainstream as novelty acts (Chubby Checker, Gary U.S. Bonds, The Coasters, Fats Domino), slow dance serenaders (The Platters), and nonthreatening girl groups such as The Supremes and The Shirelles.He was clearly backed by ABC when he appeared before the committee in 1960. (This likely had something to do with the fact that while Freed’s broadcasts brought the network annual revenues of $200,000, it earned $12 million from Clark’s show.) Flanked by high-powered legal talent and a statistician, Dick Clark dazzled committee members with non sequiturs and masterful deflection.Going into the hearings, he had divested himself of financial interests in at least 33 conflict-of-interest music business enterprises. His professional numbers man produced charts and figures demonstrating that of all the records spun on his programs, Clark had a pecuniary stake in only 27 percent, and that those records attained a popularity rating of only 23 percent. While acknowledging that from time to time he may have received compensation for extramural music-connected services, Clark respectfully but firmly denied ever having taken payola or having broken the law, saying this was just the way the industry works.In the end, Subcommittee Chair Oren Harris agreed, saying of his earnest and seemingly clean-cut witness, “I don’t think you are the inventor of the system, I think you are the product. Obviously, you’re a fine young man.”Rather than end the broadcaster’s career, the payola investigations boosted it. His entertainment empire expanded to include production, distribution, publishing, promotion, pop and country music awards, quiz shows, and “Dick Clark’s Rockin’ New Years Eve.” As the pop cultural revolution of the ’60s took a political turn, embracing the British revolution and psychedelics and turning against white-bread and bubble gum rock, Clark was well-positioned to concentrate on the business end of the business.When he died at 82 in Malibu on April 18, Richard Wagstaff Clark was a multimillionaire dozens of times over and a universally acclaimed cultural icon. Freed, after finally pleading guilty in 1963 to two of 99 counts of commercial bribery, was sentenced to pay a $300 fine and a six-month suspended sentence, after which he was put up on charges of federal income tax evasion. He thereafter descended into a spiral of itinerant radio gigs, alcohol addiction and isolation. He died in 1965, aged 43, of cirrhosis of the liver, without a pot to piss in.In differing ways, both men were avatars of interracial crossover and cultural diversity, and—even if unwittingly—agents of political change. One was a smooth huckster and commercially savvy entrepreneur; the other embodied crude raw energy attuned more to music and soul than to self-preservation and business. To progress, America needed both. For that, Dick Clark merits such acknowledgment and deserves praise. But it’s Freed who gets my everlasting kaddish.