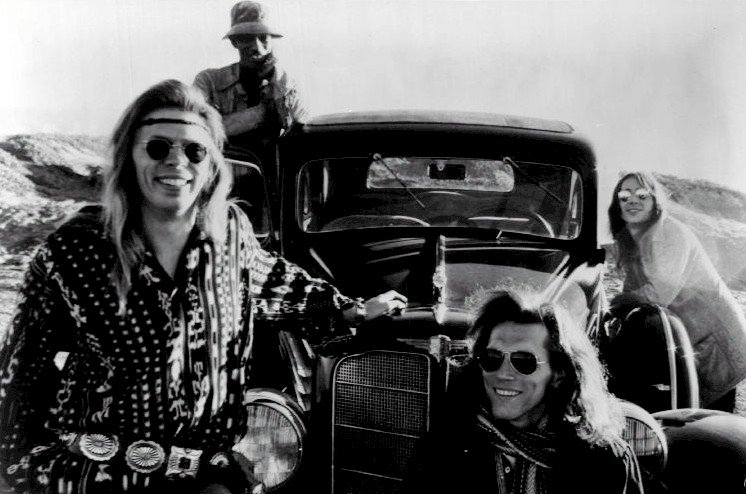

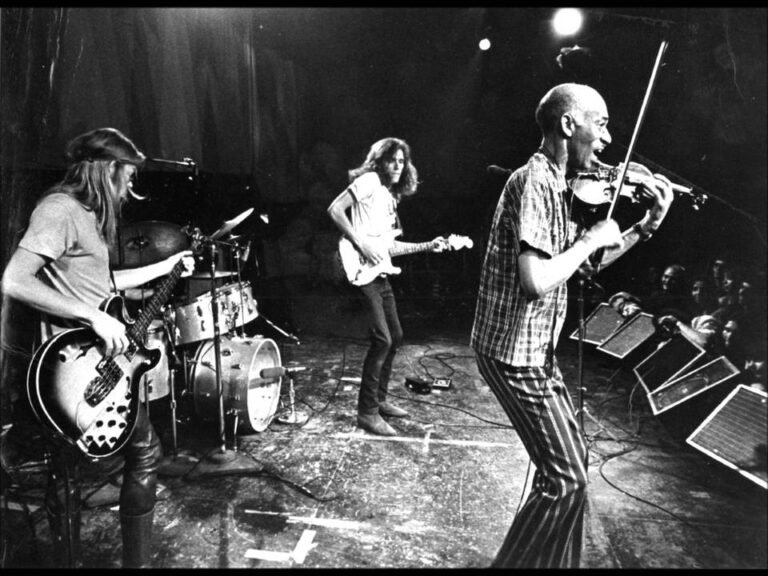

In the fall of 1992, I decided to drive the Bimmer to Florida. It was still my old man’s car and he hadn’t gotten the stereo wiring figured out. That was okay; I had good company on the way and didn’t need to listen to anything but another human voice.When the car broke down outside of Panama City, a farmer stopped where we were stranded on the side of the road. He figured out what was wrong; we were back on the road just before sunset. I changed the oil in Tampa, drove across “Alligator Alley” and dropped my friend off at Miami International.At first, the way back was lonely. I stopped by a rest stop outside of Orlando and fiddled with the radio. There was a cassette tape called Quah, by Jorma Kaukonen stuck in it. After sweating and swearing over the mess for about half an hour, I got the tape deck to work and it began playing the first side of Jorma’s first solo effort after leaving Jefferson Airplane.First came “Genesis,” a song about love, loss and a crossing into the future. When the auto-reverse feature kicked in and the second side began with “I am the Light of This World,” a stunningly syncopated, traditional blues piece about the mystical transformation of a man named Jesus Christ, I knew I would be able to find my way back to Burque.When I got there, I dug into the Jefferson Airplane catalog. I buried myself in Hot Tuna, the band Kaukonen formed with Airplane bassist Jack Casady when both saw the end of their psychedelic flight approaching.Years later, I got a chance to speak with the man who made my trip home possible. Of course he’s still jamming, turning out beautifully intricate tunes filled with longing, awesome fingerpicking and the deep, plaintive voice of America. He told me he’s bringing his band to New Mexico this weekend for the first ever Madrid Ballpark Folk and Blues Festival. I told him that was damn good, that I couldn’t wait to hear him play.Jorma and I talked about music, heroic happenstance and psychedelic situations too. Here’s a transcript of that conversation I had with the man who flew with an awesome airplane, landed somewhere in America’s heartland and made his name as a guitar god.Alibi: Have you ever flown into Albuquerque?Jorma: Yes, but not as much as often as I’d have liked to. You live in one of the most beautiful places in the world and I am excited to be coming out there.I grew up listening to Jefferson Airplane and Hot Tuna. I’ve got this whole story about Quah. And now, here I am talking to you. That’s important to me. What’s important to you musically right now?I’m one of the luckiest guys in the world. I’ve always been able to play the music I love. We’ve done some electric stuff, some folk music, and I love it all. To be able to continue with my storytelling, whether that story is told by music or through the words—and have folks like you still wanting to hear them—is unbelievable!Your music has a sharp narrative focus, in addition to the fine fingerpicking technique that you’ve mastered. Tell me about the guitar part.It’s like a multi-layered conversation. It’s an odd corner of the musical universe. I love to teach the technique. My wife and I have a school in Ohio called the Fur Peace Ranch that focuses on musical development. To be able to pass on some of this cool stuff that I’ve learned over the years, that’s my real goal. One of my funny quotes is, “I loved Elvis, but he couldn’t fingerpick.” Ironically, Ike Everly, the Everly Brothers’ father, could fingerpick and played with folks like Merle Travis and Mother Maybelle [Carter]. Those were big influences for me. The fingerpicking thing is something that guys like me can really relate to; we can geek out on it until the cows come home.What initially interested you in this style of guitar playing?I started playing the guitar when I was 14 or 15. I just wanted to play songs. The songs I wanted to play tended to be simple country songs. Lots of Carter Family pieces. I loved the sound of the guitar. There were certain qualities about the timbre of a solo acoustic guitar that just set me on fire. [Legendary bluesman] Reverend Gary Davis talked about how guitarists have three hands. One hand, the left hand, curls around the fret-board to make notes. The right hand is actually two hands. The thumb is roughly analogous to a pianist’s left hand, it handles the bass part; the rest of the fingers define a melody.So once you decided on and began perfecting your technique, you left the East Coast and ended up in San Francisco, where you got deeply involved with the first generation of psychedelic rock. How did that happen?I’m an accidental tourist. I moved to California in 1962 to attend UC Santa Clara. I’d only been fingerpicking for a couple of years. The first weekend I was out there they had a hootenanny. Those sorts of dances and accompanying musical performances were very popular in California in the early ‘60s. I met Janis Joplin, Jerry Garcia and Ron McKernan. We were all folkies. For some reason we all got interested in rock and roll. At the time it seemed like a seamless transition. In retrospect it seems like a huge leap, but really it was a natural evolution. Jerry and Ron’s first band, The Warlocks, was straight-up rock and roll. But psychedelics were legal in 1962 and as you know, musicians, given their nature, love to experiment. Those two factors changed everything.How did experiences like that lead you to Jefferson Airplane?The year I moved to Santa Clara, a friend of mine introduced me to a local folkie named Paul Kantner. We became friends and a couple years later he asked if I had a guitar and did I want to play in his band. My father was revolted for a while until he realized we were playing real music. Now I find it funny, in a good way, that the music we discovered accidentally, through experimentation and collaboration, became a genre within rock and roll. As the era ended and the Airplane began coming apart, what happened?We were such a bunch of disparate characters, but we did have a unified vision, wanted to make music together. We always supported each other’s artistic choices. And we practiced relentlessly, 8-10 hours a day. Toward the end of that, when Jack (Casady) and I left the band to form Hot Tuna, I didn’t feel that sort of familial cohesiveness anymore. Paul [Kantner] rest his soul, may disagree, but it was time to move on.So that was when Hot Tuna took off, right?Again, it was just fortuitous syncronicity. Jack and I had been playing together since 1958. We went to the same high school in D.C. We had been doing what became Hot Tuna in hotel rooms, occasionally on stage, for years. As the Airplane was becoming less loving, the Hot Tuna thing just confirmed how much Jack and I dug music. We started playing all the time. It was another natural transition.Of all that work with the Airplane and with Hot Tuna, what’s the truest expression of your musical vision?I’m really fortunate because I’ve never made an album I’ve been ashamed of. The first live Hot Tuna record is still great. I really like Burgers, our first studio album. On our next album Jack and I are thinking of going back to basics: a live, in-studio recording without overdubs.What’s the Hot Tuna audience like now? I know Gen-Xers and boomers really dig your style, but how do you relate to younger audiences?Obviously some people have our music as part of the soundtracks of their lives. But a lot of really young people come out to our gigs and they love to hear us play. We play good, but there’re a lot of dudes who play good. Our music is honest, we’re not bullshitting around man. We’re not posing; we’re telling people how we feel, and that makes our audiences feel good. Even if you weren’t lost in the ‘60s or ‘70s you can appreciate that sort of vibe.

Madrid Ballpark Folk and Blues FestivalFeaturing Hot TunaSunday July 10 • 2pm-9pmOscar Huber Memorial Ballpark • NM Highway 14Tickets: $16-42 at brownpapertickets.com