What is it that makes a record—any record—great?Could it be the production quality that gets defined with precision in the studio? Or what about authenticity? Does a recording artist have to demonstrate a certain amount of authentic flavor—whether that authenticity is derived from experience or not—in their creative efforts?And what about instrumentality? Are good chops the key to cutting records that are super-fine and thoroughly listenable?The fact is defining the qualities that go into forging a great record on the rock and roll fire can be a trying task. There are elusive qualities to excellence that speak only through the sounds and songs held captive forever but only ephemerally experienced through listening.And so it goes with the hundreds or thousands of local recordings that appear and then disappear on the Albuquerque musical horizon. Some are meh. A few are good, but once in a while a local artist records pop music that is catchy, quirky and complex enough to warrant further investigation.And sometimes, one listen is all it takes.Such is the case with Robert Bruce Jackson Caruthers. A recent Albuquerque transplant, Caruthers grew up in a suburb of Boston, Mass., listening to Switched-On Bach, Carole King, Burt Bacharach, Joni Mitchell and Simon and Garfunkel. He also spent time learning the harpsichord intro to Barry White’s “I’m Gonna Love You Just a Little More Baby.”Flash forward to the year 2020. Caruthers, a private man with deeply beautiful musical ideas, awesome execution and a diagnosis of paranoid schizophrenia, has just released four very brilliant rock records through Bandcamp. After hearing those works, Weekly Alibi invited the artist to stop by and talk about the music he makes.Weekly Alibi: Robert, could you please tell our readers about your story and the music that resulted?Robert Bruce Jackson Caruthers: What’s going to happen with my next album is that I’m going to talk a lot about—it’s going to be through monologues—myself. One of the themes is going to be mental illness. I have paranoid schizophrenia.How does that affect your everyday life and creative process?Recently, I tried working at a local grocery store. And it didn’t work out because of my disability. I take a Olanzapine for the schizophrenia, but the paranoia I had to work out on my own. It makes me a really disruptive part of any workplace.How does music help with that healing process?Music works for me. But I also found that I might be able to make a go with it, with the music, thanks to people who are listening to my records on Bandcamp.Your music is really fascinating for many reasons. It’s very informed for one thing. You have really classic influences, like Joni Mitchell, for example.She’s great, but you just couldn’t grow up in the ’70s or ’80s without hearing The Who. You couldn’t escape them, they were everywhere.Yeah, they had a great live show back in the day, too.I never got to see them in concert but I have seen R.E.M. and The Ramones, those were very important shows for me.How did these musical experiences play a role in you becoming such a superlative songwriter?It’s given me a foundation, of course. An idea. They all use the same kind of musical structure, you know, verse/chorus, verse/chorus. So I learned the basic structure of pop and rock tunes, then I learned the chord progressions, whether they be 1-4-5 or or 1-6-4-5 …It’s always good to throw in that 6, it makes jazz or something like that.Or if you want to do the Pachelbel’s Canon thing. I just kind of absorbed those things, almost like through osmosis. I haven’t really started even thinking about music.So does your process involve some sort of subconscious element? The music that comes from you, is it intentional? Do you feel like you’re absorbing all of this information and then reconstructing it as original art? How does that work?That’s it. I absorbed a lot of it as a kid. I didn’t know what I was hearing but somehow it stuck to me, the basics anyway. But the way I do things now is very methodical, very calculated.Tell me more.I will riff on a topic, then write a story or essay based on that. And then a poem follows and I turn the poem into lyrics. Then I set the lyrics to music.And that’s a process you’ve followed throughout this past year’s four album releases?Well, the first three were from stuff I had already done and written about; there were a few things I re-did in the studio. The last one, Commonplace Items For Extraordinary Tasks, I used that process I just described extensively. And I’m using the process for my new record, too. I’m trying to—it’s very calculated—but I think music really is a calculated thing, unless you’re a jazz player, unless you’re improvising. Jazz players often practice a lot and that’s the calculated part of their process.One of the fascinating things about your recent recordings is a deliberately pronounced pop aesthetic. I don’t want to issue any comparatives, but what came out seems similar to the intent of bands like Guided By Voices—who by the way were very much influenced by Pete Townshend and company.Oh, okay. That’s interesting because for the past year, I kinda kept myself away from popular music. I didn’t want the influence. I wanted to develop a sound that is uniquely mine.Let’s talk about how that idea influenced your new album. When is that going to drop?The new record will be coming out during the first part of June. You’ll probably hear about it the month before. That’s going to be about life on the edges and how that relates to basic human principles.Does that include your health experiences?Yes, very much so. But also—do you know the book by Katherine Boo called Behind the Beautiful Forevers? It’s about a city in India, a slum city built behind an airport. There’s a wall so the people at the airport can’t see it. And I wrote a song about someone living there.Does the new album also reflect where you are headed now?It’s a hopeful work. It ends on a hopeful note that says if we start noticing what’s good right now, our lives improve. We don’t have to go to the edge to find that happiness.Have you ever heard the old artists’ axiom “Great art only happens under duress?”I’ve heard that, but I don’t know if it’s true.I’m beginning to think it’s not so true. It doesn’t have to be that way, one doesn’t always have to suffer for one’s art, right?You don’t have to suffer. Carly Simon is a great example. I recently read a review about her music in The New Yorker. The reviewer was putting her down because Simon was a rich girl who never suffered. But in my opinion, she makes great music.“That’s The Way I’ve Always Heard It Should Be” is one of popular music’s most shiny gems, it’s true. It’s the perfect pop ballad.Yes! It’s really well done. The music and lyrics go together so well. And she didn’t have to suffer to make that record, she just had to use her noggin to analyze her life and her parent’s marriage.You said that your work is hopeful. What are you hopeful about?Well, Albuquerque is a great place, hands down. When my husband and I moved here, Daniel was like, “We’re not leaving!” That’s probably because he also rode 2,000 miles on a Greyhound bus to get here. But this is a great town.It’s gritty around the edges, but it’s a wonderful stopping point.And it’s that grit. It’s that grittiness that makes it a great town. You have to know what it is that makes a town special. We shouldn’t damage that.So, are you writing about Albuquerque now?That’s a great idea! I do have a song about an earthship, about a woman who finds herself through an earthship. But that’s more about Taos. I do see certain people here and think, “I’ve got to write about this.”This is a very fertile ground for inspiration.We came out here because we have friends who live out here. But as I came to live here, I began to feel accepted. And I know that when someplace accepts you, you don’t turn your back.What’s next, Robert?I’m completely DIY. The last four albums and the new album are going to be done on a 2015 Mac running Logic Pro X. But given that, would I like to have an actual producer or engineer? Absolutely.In the end, what is your music really about?All of it is about being human. The purpose of music, at least for me, is that it should illuminate something in the listener’s brain. And if they understand themselves or their world more because of that illumination, then the music has done its job. That’s what my music aims to do.

Robert Bruce Jackson Caruthers

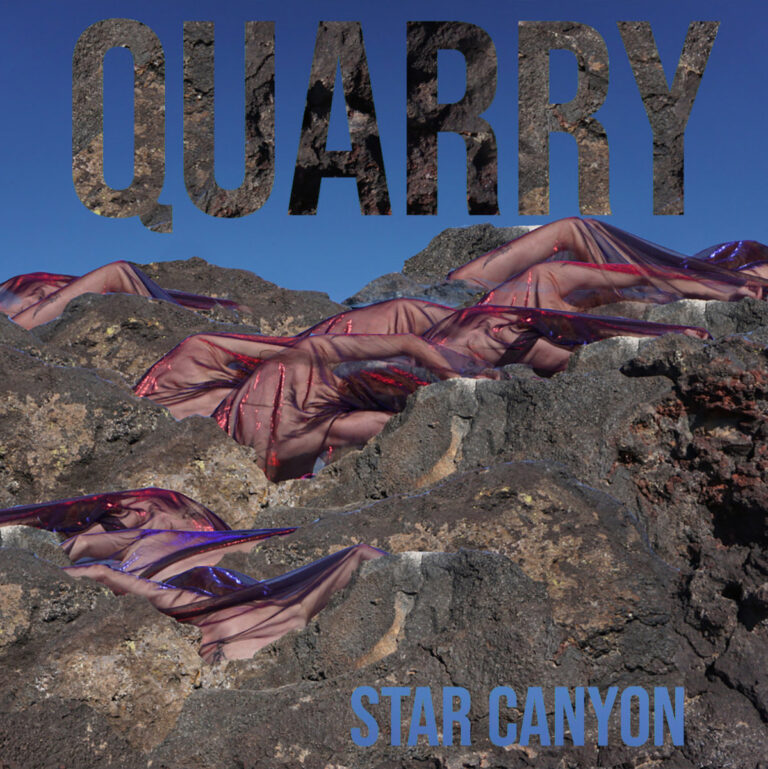

on Bandcamp atrobertjacksoncaruthers.bandcamp.com