Revolutions Per Century: A Brief History Of American Protest Music

A Brief History Of American Protest Music

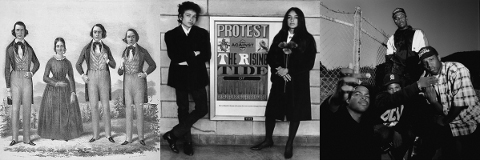

From left, the Hutchinson Family Singers, Bob Dylan and Joan Baez and N.W.A