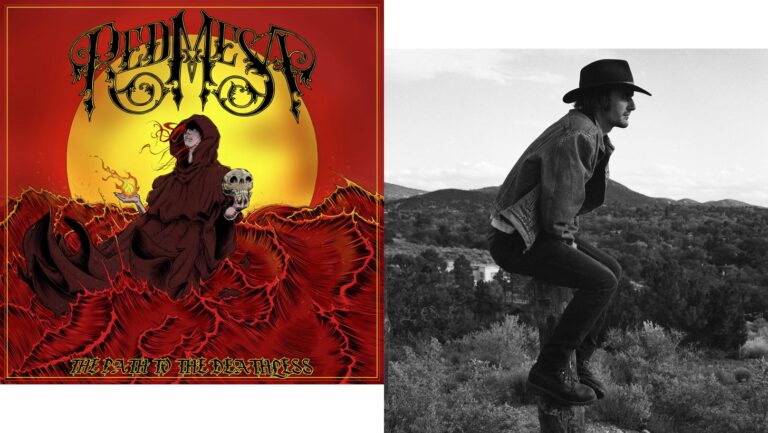

Raven Chacon spends a lot of time in airports. In the past couple weeks, he unveiled a solo sound art installation at Toronto’s A Space Gallery and joined fellow Postcommodity art collective members at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts for the premiere of a four-channel video installation, “Na’nízhoozhí Da’nijahigi Na’a’ahi (Gallup Motel Butchering).”Chacon works as a solo artist, runs Southwest-based micro record label Sicksicksick Distro, serves in the curation collective at Small Engine Gallery and performs in several bands (Death Convention Singers, Tenderizor, KILT, Mesa Ritual). He also teaches on the Navajo and Hopi reservations, and since 2004 has organized the Native American Composer Apprenticeship Project, which culminates every year with the Grand Canyon Music Festival. It’s one of 14 winners of the National Art and Humanities Youth Program Awards. On Nov. 2, he and two others from the project will be accepting the honor from Michelle Obama in D.C. Meanwhile, on Saturday, he and Mesa Ritual partner William Fowler Collins perform at the opening installment of the High Mayhem Emerging Arts fall series. High Mayhem celebrates 10 years of showcasing Nuevo Mexicano and international sound art at the four-weekend 2011 series. Chacon and Collins hail from divergent homelands—Chacon from Chinle, Ariz., on the Navajo reservation and Collins from the Bay Area. But the two share formal musical education, a decidedly nonacademic approach to composing and a passion for collaboration. The Alibi caught up with Chacon by phone during his layover in Dallas to talk Postcommodity, Mesa Ritual and High Mayhem. What’s Postcommodity’s “Gallup Motel Butchering” installation all about? That piece started as a story I’d heard in which a Navajo family down in Phoenix acquired a sheep to take back home to northern Arizona. They were staying in a Motel 6 and realized they had some relatives in town they wanted to give some meat to. They ended up just butchering the sheep in the Motel 6. It’s a story you hear often—of people just needing to butcher immediately. So what we wanted to do is recreate that situation to show a reality of displacement of American Indian people, while also showing an emergence that might follow Navajo creation stories. This woman is doing a practice that she could be doing anywhere else, but there happened to be a motel built around that site. It’s not even about a changing of the site but about turning it into a non-place. Are you excited about performing at High Mayhem? We’re happy to be asked to do this again. I’ve played the festival two times in the past. And it’s great that they’re doing this [in Santa Fe], because it does mirror what we’re trying to do [in Albuquerque]. They work hard to be able to gather resources to bring international artists. It’s inspiring to us because [laughs] we just don’t have our shit together like they do. And, between the two cities, it’s bringing a lot of good people and performances. Can you describe Mesa Ritual? What we play is what people might call electronic music because it does utilize some electronic effects. But it’s mostly just electric music. He has an electric guitar that gets processed, and I have a lot of analog electric equipment, such as tone generators and microphones that I build. Some of our recordings have undergone a highly composed process, and live, we still work with those forms. But, for the most part, it’s loosely based around structures that we’ve been rehearsing. What does it sound like? Sonically, even though it’s just a group of two, Mesa Ritual encompasses the widest frequency range—meaning the lowest and highest tones you can get to—that one might hear in music. Something we definitely do is physically spread out our sound. … And it is noise, but I’d describe it as very clean noise. It can be harsh but it’s still a very direct sound—not at all muddled or washed out.